We recently spent three days in New York City.

As I read the last line of Mary Oliver’s poem “Heavy”—”a love to which there is no reply”—it occurred to me that this describes my love for NYC. You can love NYC, but NYC doesn’t love you back. NYC doesn’t actually give a shit about you; the city is completely self-absorbed, and that’s just fine. It’s all part of the city’s mystique, its swirling, pigeon-flocked, neon-lit-glass-and-steel, rapid-fire, whirling-dervish, creative vibration.

We stayed at a sweet hotel in the Flatiron district, saw wonderful exhibits at the Whitney and the Met, watched Kenneth Branagh as King Lear, went to a comedy show where five hilarious stand-up comedians made me laugh for ninety minutes. I loved all of it, every minute. But a few small vignettes stay with me and keep breaking the surface of my thoughts.

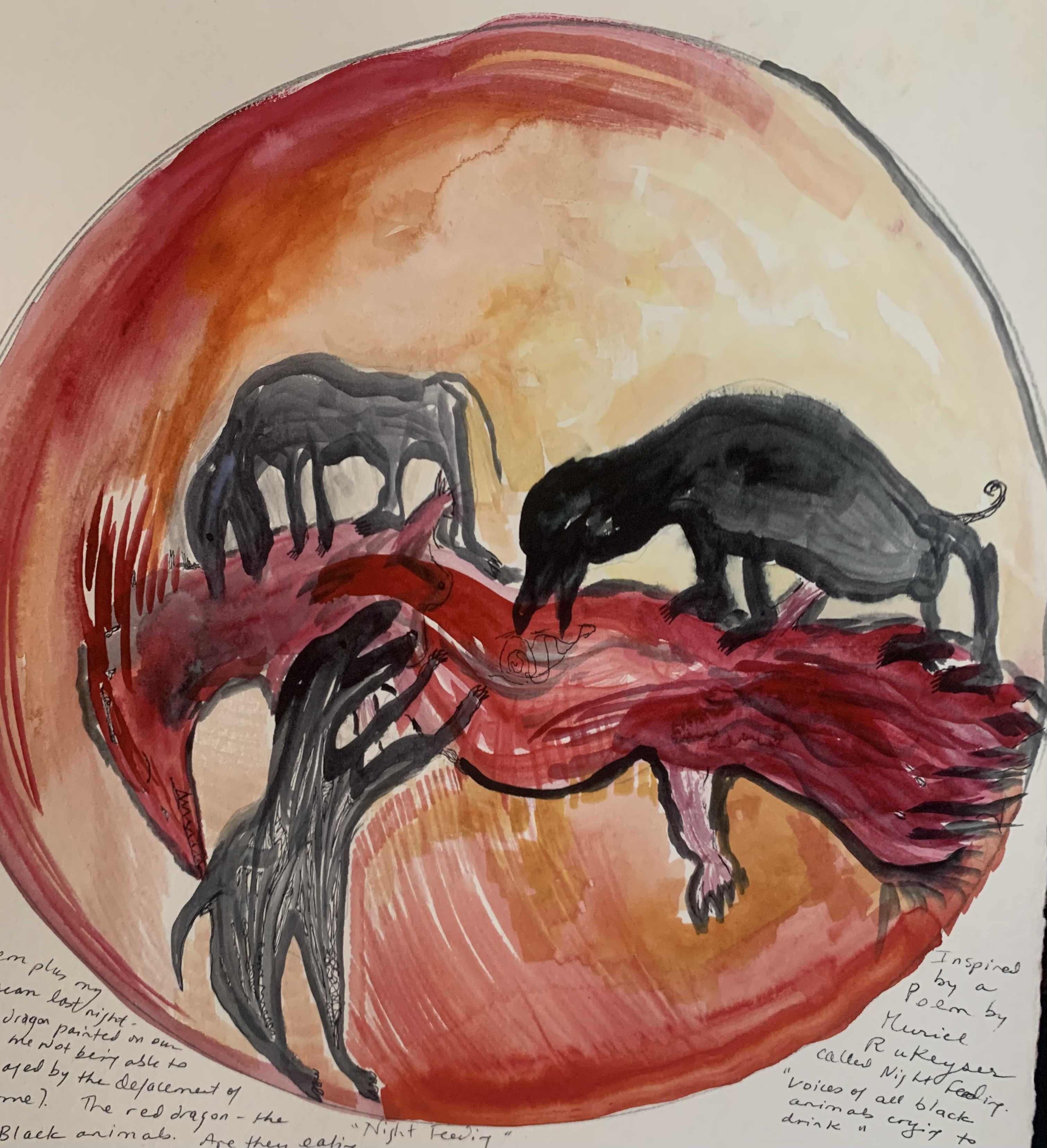

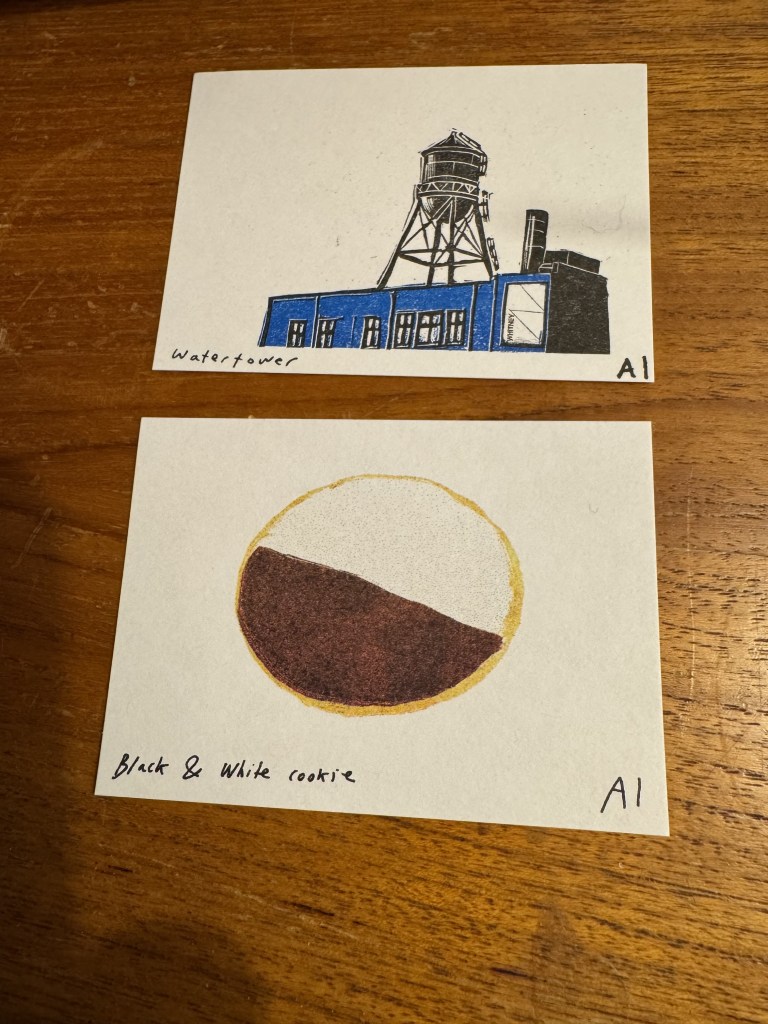

One dollar for an original print

In the Whitney Museum gift shop there’s a vending machine at one end where you can slide four quarters into the slots, push, and out pops an original print of some NYC iconic object or scene by Ana Inciardi. We put our quarters in, and now we own two tiny prints (2.5 inches by 3.5 inches): a black and white cookie and a NYC water tower. Inciardi is kind of genius, isn’t she? I don’t know if she profits from this—surely a print for a dollar is not netting her much money. But it is such a delightful thing to encounter: a vending machine dispensing original art. I want art vending machines to be installed everywhere, machines where you insert coins and receive poems, collages, small clay sculptures, watercolours, flash fiction, holograms, fabric art, tarot cards… Can you see it?

The women’s washroom at Barnes and Noble

To use the washroom at the Fifth Avenue location of Barnes and Noble, you must first purchase something. At the bottom of your receipt is the bathroom code. I bought The Temporary, a novel by Rachel Cusk, an author I have been wanting to read (the novel is wonderfully written, but very depressing). I then used the code to enter the women’s washroom, where there was a line up for the two working stalls (there always seems to be one stall with a scrawled “out of order” sign). A woman of colour (#1) exited one of the stalls, but the next person in line (white woman) looked in, then withdrew with a look of disgust on her face. Woman #1, was busy washing her hands. I said to woman #2, “what’s the problem? You’re not going in?” Woman #2, not making eye contact with me, said cooly, “they got stuff all over the seat.” I went into the stall and saw a fine spray of water droplets on the seat, likely created by the toilet’s back spray. Quickly removed with a wipe of toilet paper. The venomous way woman #2 said “they got stuff all over the seat” implied something terrible, perhaps excrement smeared everywhere. Her contemptuous reaction was so overblown and ridiculous—it felt symbolic of a rising wave of incivility and prejudice in (American) society. Ugh.

Four girls draw a statue

I loved the two exhibits we spent time with at the Metropolitan Museum of Art: Mandalas, Mapping the Buddhist Art of Tibet and Mexican Prints at the Vanguard. As we left the museum, passing through the Leon Levy and Shelby White court filled with ancient Greek and Roman statues, I saw four teen girls sitting on the marble floor in front of a bench, absorbed in drawing a statue of a nude man. This is what I will remember from the trip… their bowed heads, their silent engagement with the statue and with each other. A refreshing palate cleanser after bathroom woman #2’s remark. Oh, and the Joan of Arc by Jules Bastien-Lepage (1879): her face had me swooning.

Docent at the Met

We got a bit lost after the Mandala exhibit and asked a docent for help locate the gallery where the Mexican prints were on display. She led us rapidly through throngs of people, and I told her my mother had been a docent for years at the Art Gallery of Ontario (I had many moments of thinking of my mom in NYC—we visited the city together in my early twenties and saw, among other things, Zero Mostel in Fiddler on the Roof). The docent explained she had to do highlights tours for two years before they let her specialize in anything. I asked her what she specializes in now. Arms and armour, she answered. And I get to have another speciality, she said, but I am taking a break. Evidently, it’s exhausting to learn all there is to learn about the arms and armour in the Met’s extensive collection.

Pumpkin Pie at the Malibu Diner

Before the show at Gotham Comedy Club, West 23rd and 7th Avenue, we ate dinner at the Malibu Diner across the street. An old-fashioned American diner with a huge, laminated menu, plenty of booths with red vinyl benches, low chrome stools facing the long counter. All of the waiters spoke Spanish among themselves. When our waiter brought my twice-baked potato, I said Gracias Señor, and then he started to speak to me in Spanish, and I had to explain that I only know a few words. He laughed.

We paid for our meals and went to the club, but we were early. The woman said come back in half an hour; they were running late. Where to go? The cold wind bit our cheeks that night. So, we returned to the diner, where the waiters welcomed us like old friends. Come, come to the back, sit in this booth, where you won’t feel the wind that sneaks in whenever somebody opens the door. It’s warm back here. Our same waiter from before brought pumpkin pie with whipped cream. Sometimes eating dessert is the perfect way to pass time.

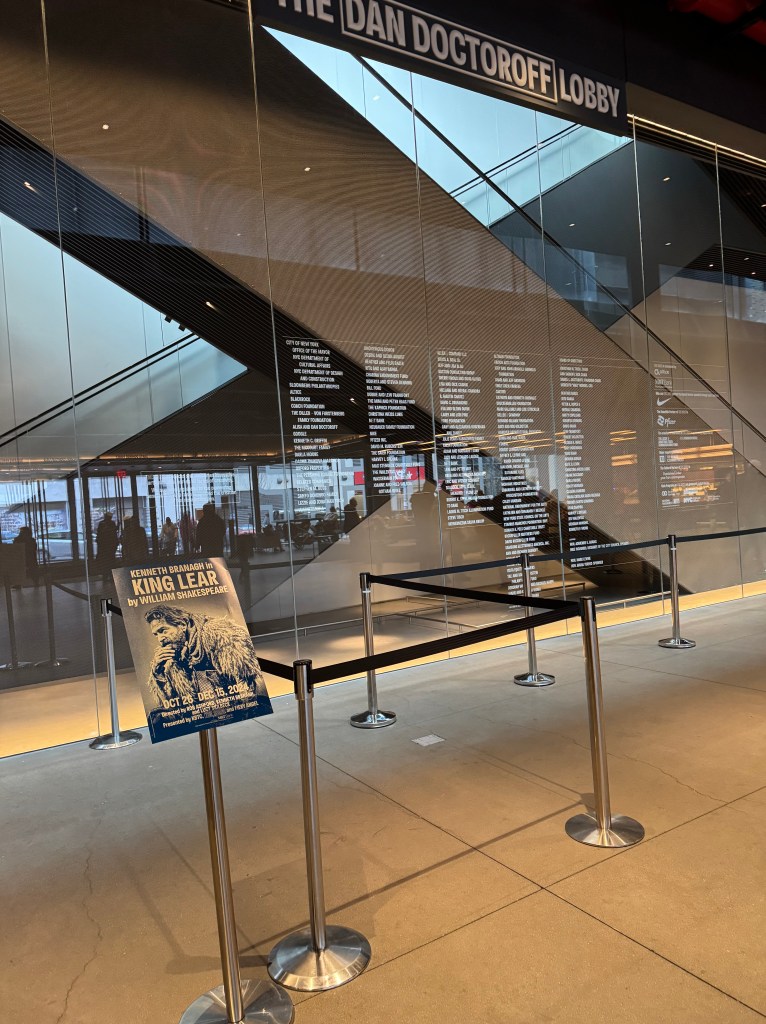

Shakespeare groupies

We took our excellent seats at the Griffin Theatre (at the Shed), where we had tickets to see King Lear. In front of us, two women about my age were taking off their coats and chatting. They started to engage us in conversation—where were we from? Did we go to a lot of Shakespeare plays? They had both lived in Atlanta and belonged to a Shakespeare reading group. When one of them moved to Baltimore, Maryland, they figured that was it—they wouldn’t see each other again. But then the Maryland woman saw an advertisement for King Lear with Kenneth Branagh and called her Atlanta friend. Why don’t I buy tickets? You can fly here. We’ll go together. So, Atlanta woman got a flight to Baltimore, and that morning they’d taken the train from Baltimore to Manhattan. We’re Shakespeare groupies, the blonde woman from Atlanta said. In April, we’re going to see Denzel Washington in Othello, said the Baltimore woman. Shakespeare groupies. I love it.

Window shopping

NYC is the best place to window shop. No need to buy a thing; just absorb the kaleidoscope of artifacts and moods rippling through glass. Mannequins wearing weird t-shirts, everything Harry Potter, bolts of cloth, soaps, sculpture, ceramics, sexy candles, life messages, and rainbow bagels.

Until next time…

We walked through Chelsea along a sidewalk that bordered a basketball court. Kids were shooting baskets on the first day of December, laughing, talking. A flock of grey pigeons passed overhead while the sun winked from behind a fringe of clouds. A bubble of pure joy passed through my body and into my head, exploding into a private smile. I love you, New York City; no reply necessary.