“When we run from our suffering we are actually running toward it.” Ajahn Chah

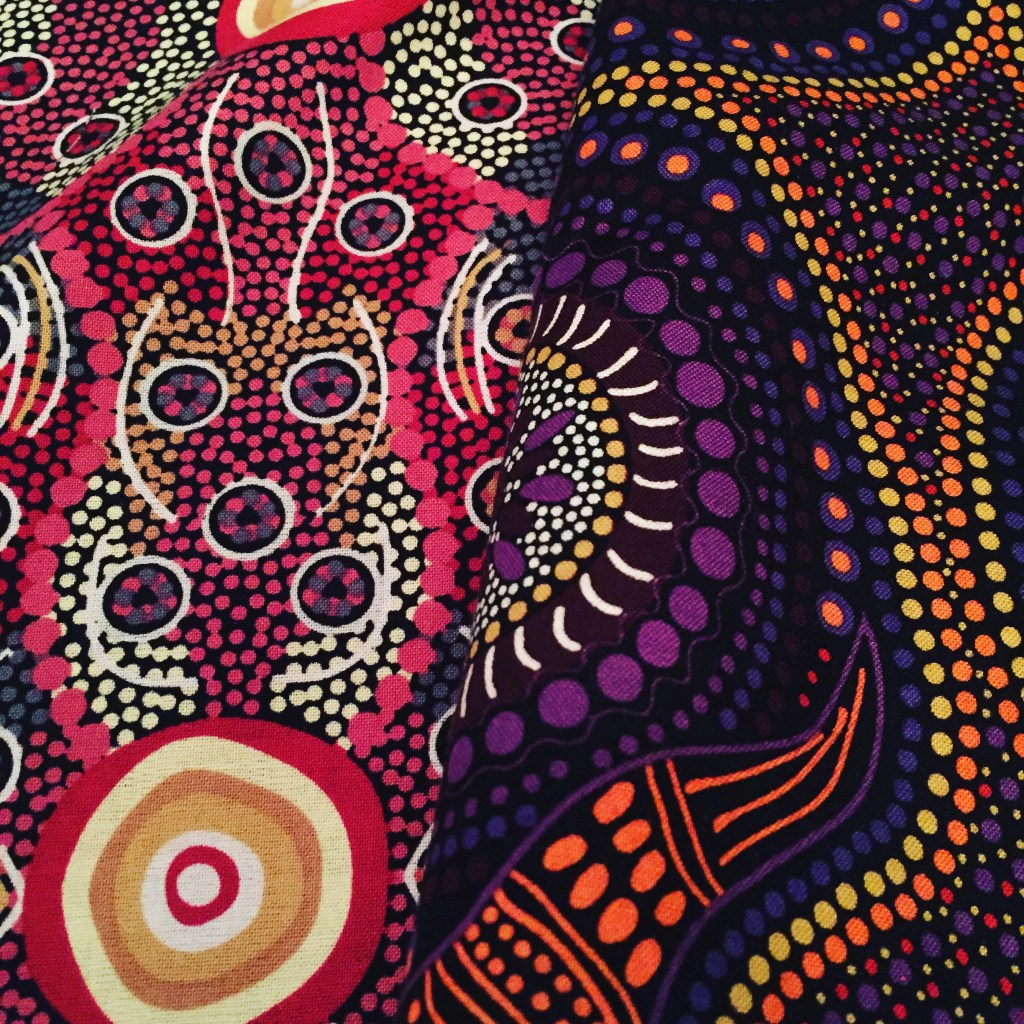

I’ve been basking in two messages from my unconscious this week. In one dream, a person wearing a bright tie-dyed shirt holds a hand lettered sign, “You are not alone.” In another dream, a young man, bearded, hugs me and whispers in my ear, “Thank you for your patience.” The messages are hackneyed, and yet they were delivered to me fresh, warm, colourful, by stately messengers. It doesn’t matter if they—the messages and the messengers—aren’t “real”; they are just as real as the people and events, the words, ideas, and things I encounter in my dream-like conscious life. And more to the point: They provide great comfort, having bathed me all week in an orange glow, a glow like that emanating from the 10,000 joys wall hanging, now installed in our stairwell.

The wall hanging seems to collect the sunlight falling in through the skylight and send back a peachy radiance. Several times now I’ve gone to flick the hall light off, thinking the switch is on when it shouldn’t be. No, the light is off, but 10,000 joys shed their own uncanny light.

When I made the piece, I kept telling myself, you don’t have to make its counterpart, 10,000 sorrows. It’s okay to just focus on joy right now. But of course, you cannot have 10,000 joys without 10,000 sorrows. I wish we taught this truth to children in kindergarten. You don’t experience joy without experiencing sorrow. And it’s okay. When you cling to joy and try to avoid sorrow, you just prolong it. I wish I’d gone to a Buddhist kindergarten, where these truths would be taught elegantly and logically, instead of being told by adults that “life isn’t fair,” which seems tawdry and cruel in comparison to the dharma.

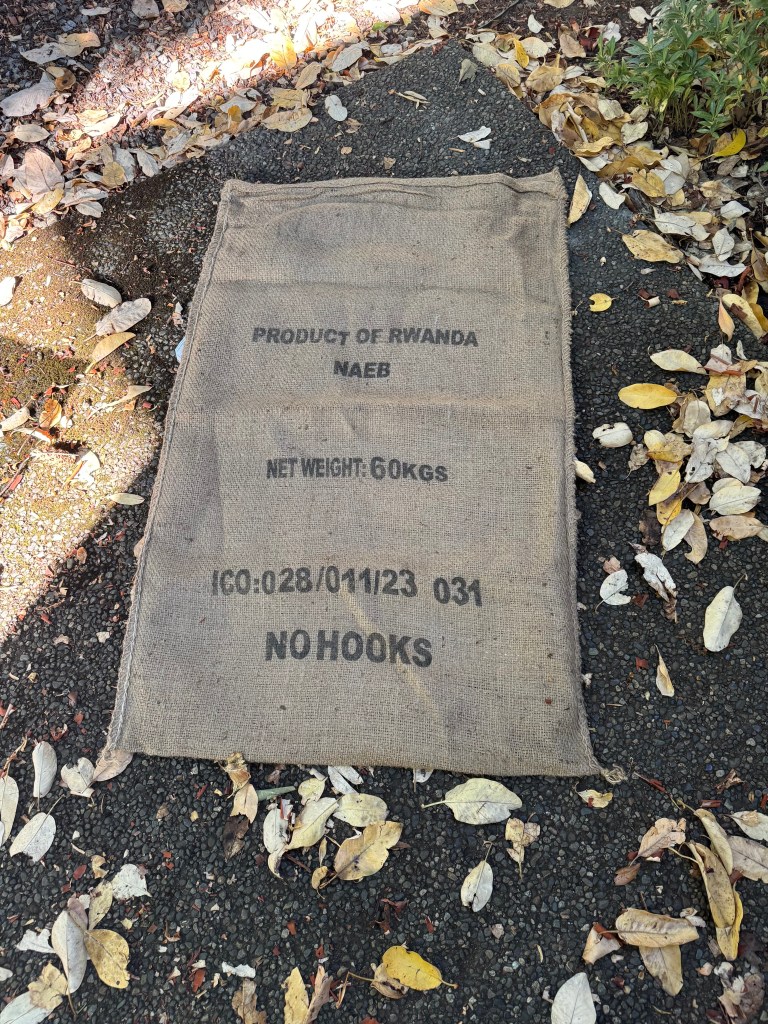

Inevitably, I am called upon to make joy’s counterpart. I had coffee with a friend yesterday at Esquimalt Roasting Company. As I waited at the counter for our lattés, I noticed a large burlap bag draped over a plastic bucket. I picked it up and showed it to the barista. Can I buy this? I asked. In my imagination, I was already picking its seams and spreading it out, a wide brown canvas for thousands of sorrows. It’s free! she responded. So now I have the backdrop for the wall hanging. I had originally thought it should be black, but brown is less dramatic than black, more subdued and complex, as sorrows often are, especially as we digest them.

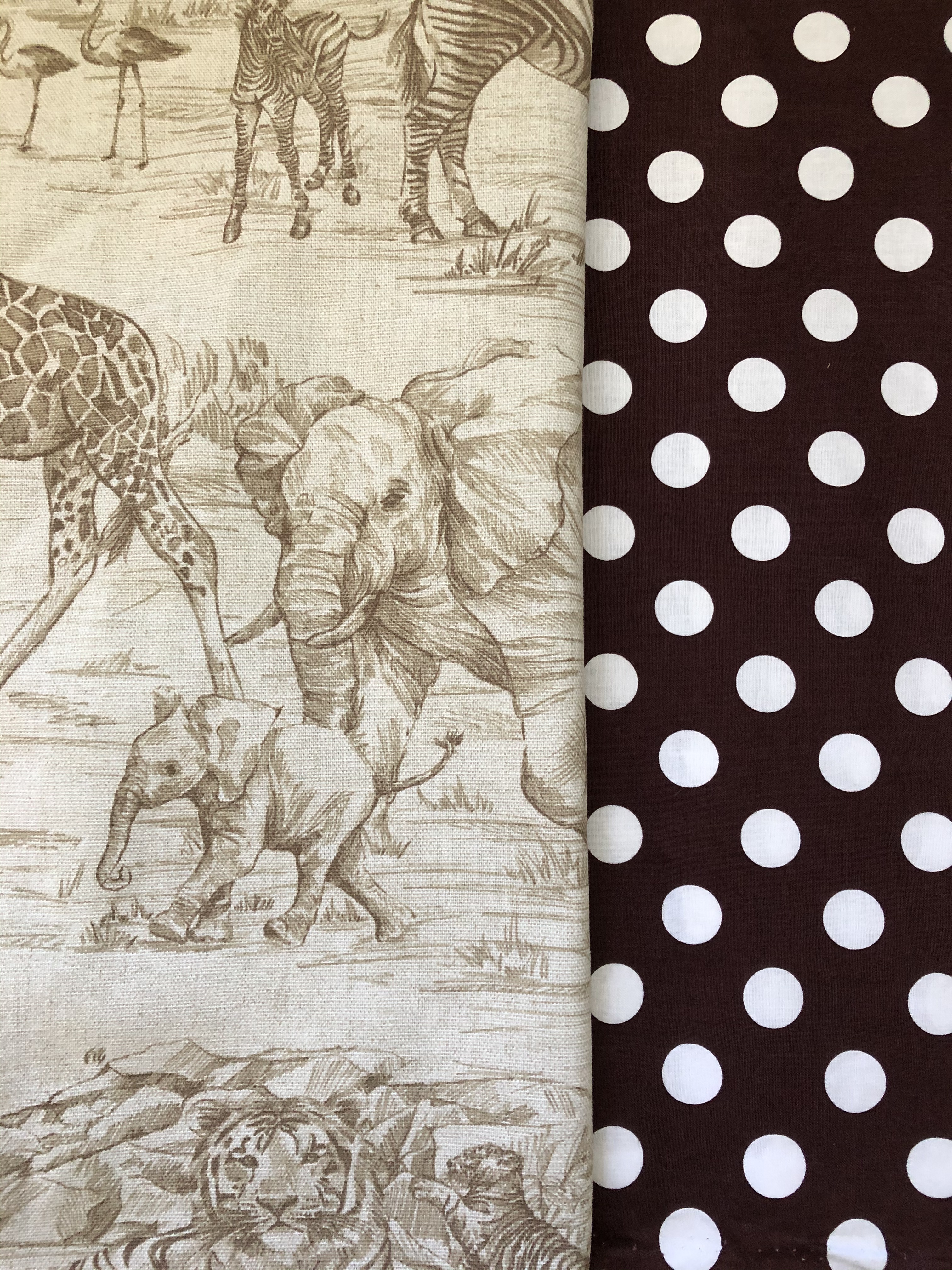

The burlap bag was pure serendipity. Another magical find was a zebra at the ReStore in Langford. Purchased for 70 cents ($1.00 but there was a 30% off sale). This zebra is majestic, dignified, kind, warm. She stands about 10 inches high. Her stripes are unrealistic, but otherwise she is a convincing animal. I dug out a stuffed toy zebra I’d kept from childhood in a box under the stairs. It’s remarkable this sixty-year old stuffed animal still stands! They now live together, mother and child, atop a bookshelf in our bedroom. I like to gaze at them from bed. Something about them feels calming, comforting. I loved my zebra striped one-piece bathing suit when I was eight years old. When I wore it, my reward was a zebra tan that was pure magic.

How to find comfort

Face fear, face grief,

crunch on them like buttered

toast, let them nourish

you. Small striped body

in the mirror, some kind of

childhood magic. Let dreams

bathe you in orange light.

Sweet’s after tastes

bitter, crying sparks a belly

laugh. Joy and sorrow

are so intertwined, you can’t

tease them apart, please

don’t waste time trying.

Practice the butterfly hug:

Hands cross collarbones,

thumbs meet, fingers tap lightly,

lightly. A comforting rhythm

will come. It will come.

For Frankie

For Frankie

Open your closet and

Open your closet and