In mid-December, I bought a green glass jug in a second-hand store, half price. My aspiration was to make a beautiful winter bouquet for my friend, Lillian. I bought a bunch of silver dollar eucalyptus and two dozen white carnations. I envisioned white wintry bursts among the silvery green, but the more I trimmed and mixed the carnations with the stems of eucalyptus, the sillier and more incoherent it looked. I took basic Ikebana but still haven’t a clue how to make flowers and plants look good.

Finally, I used only the eucalyptus, splayed out in a free-fall arrangement. I attached a few small, red shiny balls to the stems, and the effect, I hope, was Christmassy and charming, if a bit messy. Lillian said she loved it. (But what could she say, really?) I was going to throw out the unused carnations, but it seemed such a waste, so I put them in a white and blue vase and placed it in my study on a low stool covered with a blue-green cloth.

I don’t like carnations, or I didn’t think that I did. I’ve seen too many sad, slender bunches wrapped in cellophane at the mini-mart next to the hospital. They make me think of last-minute purchases for the death bed, cheap flowers that outlive the person you visited. They seem so tight, orthodox, banal. Whorls of perfect, serrated petals, every bloom the same.

But they’ve grown on me. As I spend hours in their presence, they’ve become real. You could say I’ve become intimate with them. I sit here now, the last day of the year, gazing at their fresh ordinariness. The carnation is the sturdy, faithful flower that will see you through. Perhaps they are flower of the year: commonplace as canned milk. Carnations are one-foot-in-front-of-the-other flowers. Quotidian flowers. Bread-and-butter blooms. See you through the hardest times. Last for weeks. Nothing special.

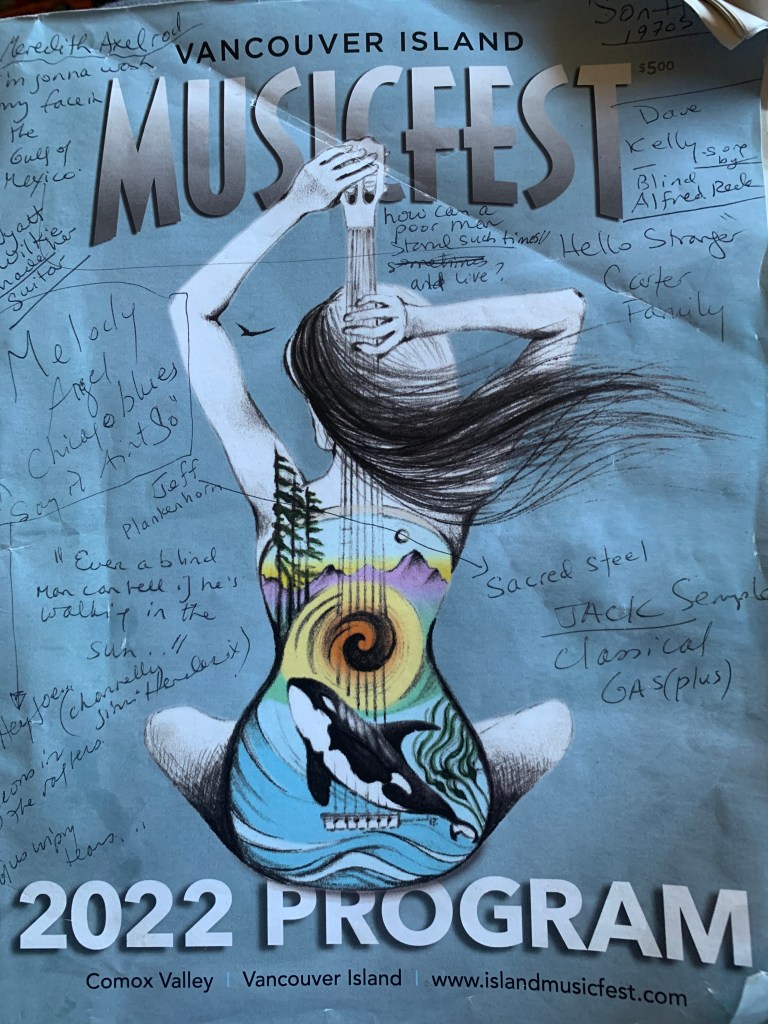

Although 2024 was my first year of so-called retirement, and thus I was given twenty additional hours each week, I wrote less, and I sewed less. (A few felt birds for family and other little felt creations, an apron, a crib quilt start, a fur-lined bag.) I did finish an editing certificate I started in 2020, which is a relief. And I made a lovely new friend and deepened existing friendships. I started a volunteer gig at a non-profit arts and crafts shop in August that has led to meeting many interesting people. Bonus: I get to surround myself with a messy profusion of materials that inspire me.

This year, I listened to probably one hundred dharma talks on Dharma Seed, with a broad aspiration of becoming more intimate with life—accepting whatever’s happening in my heart, whatever’s happening in the world. Making friends with wild mind. Accepting the truth of the way things are.

I read so many books this year. A couple that stick with me are Rebecca Solnit’s memoir, Recollections of My Nonexistence and The Age of Loneliness, a book of essays about life during the sixth extinction by Laura Marris.

Solnit writes a lot about being a woman. That’s what her title gestures toward—the peculiar “nonexistence” of being female in a patriarchy (remember mansplaining? She is behind that neologism[i]). She draws on John Berger’s 1972 Ways of Seeing, which I’ve known about for years and now am determined to read. She quotes words from him that jibe with my experience: “To be born a woman has been to be born, within an allotted and confined space, into the keeping of men. The social presence of women has developed as a result of their ingenuity in living under such tutelage with such a limited space. But this has been at the cost of a woman’s self being split into two.”

Perhaps that sounds dramatic in the Global North in 2024, but that has been my experience. Perhaps it’s different for lesbians. Perhaps it is different for women of subsequent generations, but Solnit and I were born three years apart (1961/1958), so we grew up at roughly the same time. Berger goes on,

“A woman must continually watch herself. … She has to survey everything she is and everything she does because how she appears to others, and ultimately how she appears to men, is of crucial importance for what is normally thought of as the success of her life. Her own sense of being in herself is supplanted by a sense of being appreciated as yourself by another.”

Solnit calls Berger brilliant and generous, to be able to imagine a woman’s experience, and I agree. What he writes here feels just as real as the carnations in front of me. Reading the passage and feeling its truth is freeing. No action needed, just awareness.

Similarly, truth pinged through me when I read Laura Marris writing about the age of loneliness. We become lonelier as we bear witness to the drastic reduction, or “great thinning,” of ordinary animals. Marris draws on the work of naturalist, Michael McCarthy, who writes of our baby boomer age group, “As we come to the end of our time, a different way of categorising us is beginning to manifest itself: we were the generation who, over the long course of our lives, saw the shadow fall across the face of the earth.”

Reading this series of essays, elegies to Earth as the shadow descends and animals disappear, I was gripped by a grief so deep I sat for a time and just cried. Again, the truth is freeing. Let’s not deny that this is happening. It’s really happening. We can still enjoy the beauty that is here.

In keeping with my mood of asceticism, I recently deleted my Facebook and Instagram accounts. Unlike the birds who used to sing outside my window, FB and IG will not be mourned. I feel light as I step through life with a new red pedometer safety-pinned to my leggings (the pedometer frees me from carrying a “smart” phone to count steps). Michael, Marvin, and I amble down to the beach at Thetis Cove to watch the sky change. Rippled water reflects a bank of pink clouds.

Thank you for reading. In the coming year, may you experience moments of lightness in a shadowy world.

Berger, John. 1972. Ways of Seeing. Penguin.

Marris, Laura. 2024. The Age of Loneliness: Essays. Greywolf Press.

McCarthy, Michael. 2015. The Moth Snowstorm: Nature and Joy. New York Review Books.

Solnit, Rebecca. 2020. Recollections of My Nonexistence. Viking.

[i] From Wikipedia: The term mansplaining was inspired by an essay, “Men Explain Things to Me: Facts Didn’t Get in Their Way”, written by author Rebecca Solnit and published on TomDispatch.com on 13 April 2008. In the essay, Solnit told an anecdote about a man at a party who said he had heard she had written some books. She began to talk about her most recent, on Eadweard Muybridge, whereupon the man cut her off and asked if she had “heard about the very important Muybridge book that came out this year”—not considering that it might be (as, in fact, it was) Solnit’s book. Solnit did not use the word mansplaining in the essay, but she described the phenomenon as “something every woman knows”.

A few weeks ago, I picked up Octavia Butler’s The Parable of the Sower from the cute little library on the front yard of a house around the corner. “Take a Book, Leave a Book” was painted in curlicued white letters across the blue cupboard doors. When I was a teenager, I decided I wasn’t interested in science fiction. Somehow, I only wanted to read things that were “real.” So I turned to 19th century British novels and early-mid 20th century American writers like Philip Roth and Saul Bellow. Of course I have cast my reading net much wider since then, but I still don’t tend to be drawn to science fiction or its sister genres, fantasy and horror. Yet, as I dug into Butler’s novel, I became engrossed by the young female narrator/ protagonist Lauren who is bent on survival in a dystopian America of the future. Her warrior spirit drives her to escape from the murder of her family and razing of her home in a gated community in Southern California and form a motley tribe of people all searching for safety. Due to her mother’s drug abuse, Lauren was born with hyperempathy, a disability that has her feeling other people’s pain to a debilitating degree. She develops a religion called Earthseed, whose God is Change because the only thing we can be certain of is that everything changes. What felt eerie about this novel, written in 1993, was that Butler’s portrayal of a dystopian nation read as strongly resembling Trump’s America.

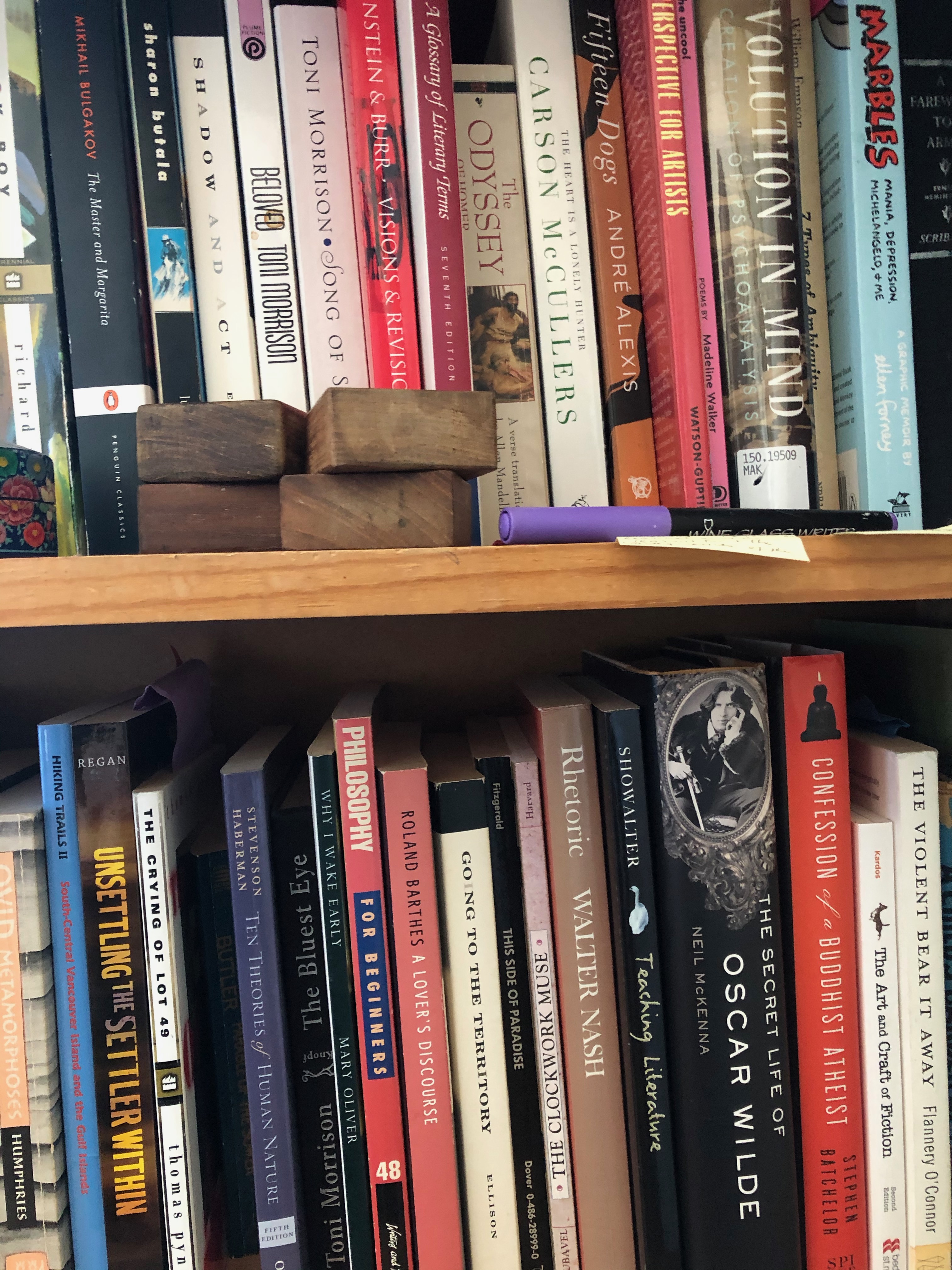

A few weeks ago, I picked up Octavia Butler’s The Parable of the Sower from the cute little library on the front yard of a house around the corner. “Take a Book, Leave a Book” was painted in curlicued white letters across the blue cupboard doors. When I was a teenager, I decided I wasn’t interested in science fiction. Somehow, I only wanted to read things that were “real.” So I turned to 19th century British novels and early-mid 20th century American writers like Philip Roth and Saul Bellow. Of course I have cast my reading net much wider since then, but I still don’t tend to be drawn to science fiction or its sister genres, fantasy and horror. Yet, as I dug into Butler’s novel, I became engrossed by the young female narrator/ protagonist Lauren who is bent on survival in a dystopian America of the future. Her warrior spirit drives her to escape from the murder of her family and razing of her home in a gated community in Southern California and form a motley tribe of people all searching for safety. Due to her mother’s drug abuse, Lauren was born with hyperempathy, a disability that has her feeling other people’s pain to a debilitating degree. She develops a religion called Earthseed, whose God is Change because the only thing we can be certain of is that everything changes. What felt eerie about this novel, written in 1993, was that Butler’s portrayal of a dystopian nation read as strongly resembling Trump’s America. I always prefer books as objects over digitized texts. I love the feel and look of books. I love to explore marginalia and marks, run my hands over bindings, examine tatters and pages folded over, text that has been underlined. The other day I picked up a well worn novel (The Lotus Eaters by Tatjana Soli) from a free library that had written in the inside cover in elegant cursive, “Property of” followed by a rectangular stamp: The Cavern Hotel and Café, El Nido, Palawan. I Googled this mysterious place and discovered it is a hotel offering pod accommodations in the Philippines. So interesting. (The next day, Trip Advisor wondered if I would like to see the current rates for staying the Cavern.)

I always prefer books as objects over digitized texts. I love the feel and look of books. I love to explore marginalia and marks, run my hands over bindings, examine tatters and pages folded over, text that has been underlined. The other day I picked up a well worn novel (The Lotus Eaters by Tatjana Soli) from a free library that had written in the inside cover in elegant cursive, “Property of” followed by a rectangular stamp: The Cavern Hotel and Café, El Nido, Palawan. I Googled this mysterious place and discovered it is a hotel offering pod accommodations in the Philippines. So interesting. (The next day, Trip Advisor wondered if I would like to see the current rates for staying the Cavern.) the dark, I enter into the world of Butler’s novel, where kindness is the last good thing, where people band together in tribes because love and human relationships are all that we have, and where impermanence is the only truth. Wait a minute, all of that is sounding familiar. Is it really the future, or is it now?

the dark, I enter into the world of Butler’s novel, where kindness is the last good thing, where people band together in tribes because love and human relationships are all that we have, and where impermanence is the only truth. Wait a minute, all of that is sounding familiar. Is it really the future, or is it now?