When I was in my forties, my mother was in her seventies. (We could rapidly figure out each other’s age because I was born when she was 30.) Those days, I had scant time for or interest in her stories. Busy with kids, negotiating the break-up of my marriage, and immersed in the chaotic life of a graduate student, I was living my life 3,000 miles away from my mother.

We talked on the phone weekly and visited once or twice a year. When she started to tell a story from the past, I often zoned out or became irritated. I didn’t really care, or I thought I’d heard it before. She sensed my impatience because eventually she stopped expecting a weekly phone call. “You sound too busy,” she said. I didn’t disagree. My forties turned to fifties; her seventies turned to eighties. We kept in touch, but calls were infrequent.

On Valentines Day, it will be six years since her death. I am 66 now, and at least a couple of times each week, I think of something I want to ask her. Some thread we dropped that I’d like to pick up again. Some mystery from her past I want to understand. Some memory I want her to clarify. (There are so many amorphous, shady memories—are they true?)

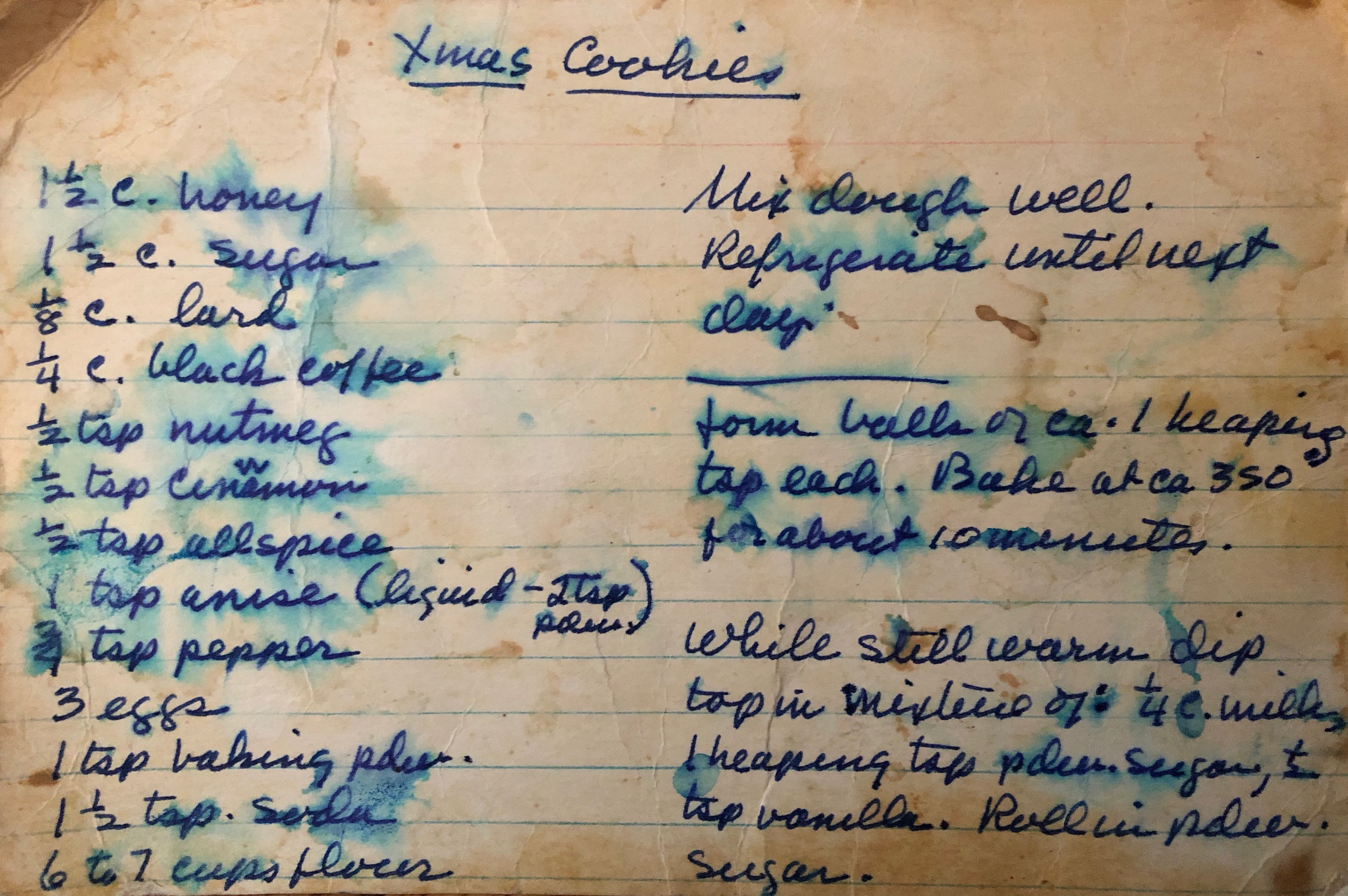

How did you make that wonderful crème caramel? I wish I’d gotten the recipe. Tell me more about the trip you took to Russia. When you returned from the trip and tried to tell me about it, I had so much on my mind I didn’t listen. But now I really want to know. And the other trips… so many European cities you visited, sometimes with groups of students, showing them great works of art and architecture. I wish you could tell me more.

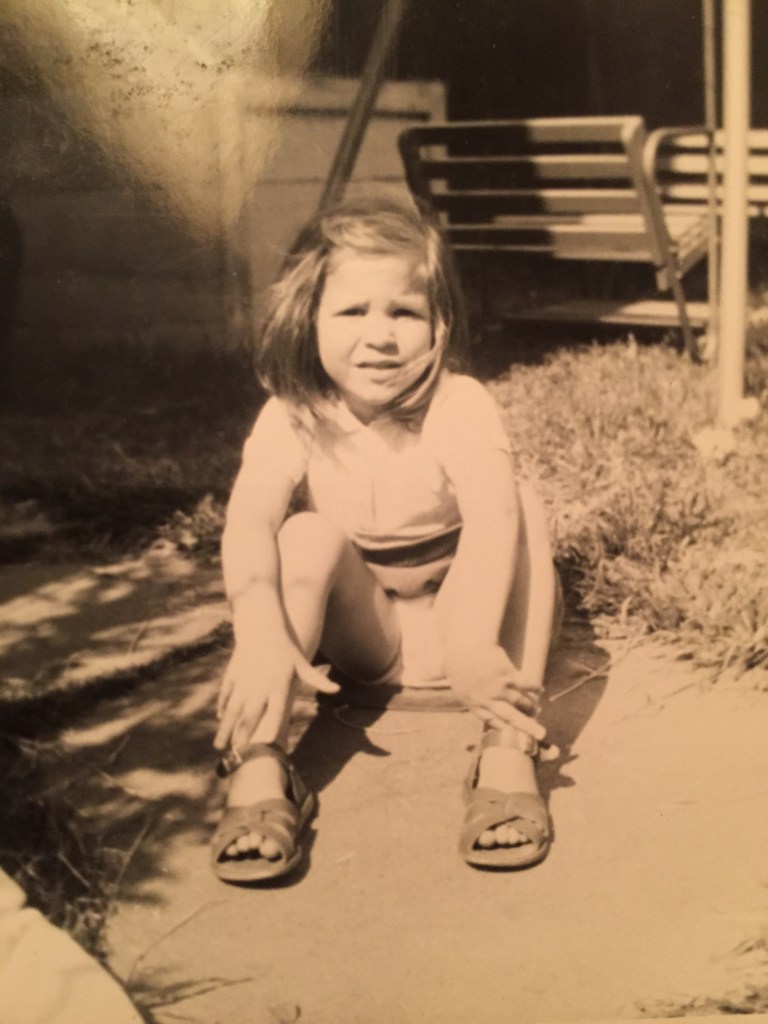

You didn’t talk to your own mother for decades. I never knew her, only met her once. Why were you estranged? Your childhood was traumatic. Is it true you missed a year of school because you didn’t have shoes to fit your feet? That you learned to drive the tractor at age nine (or was it 12) so you could help on the farm? That your dad kicked you out of the house at 17, but he’s the one you loved? Am I misremembering your narratives?

I have the old phone number in my head 416-922-9534; if only I could call, we would chat. She’d be happy to hear from me and to reminisce, I know. But she’s no longer available. The stories, too, are gone. They died with her.

I had the wherewithal to record my father talking about his life in 2014 when he was visiting (he was 87). I asked him a series of questions. Now, I am glad to have his voice preserved as he talks about his parents, being a father, his life as an academic and farmer, and formative childhood experiences. For example, he describes discovering an injured bird when he was a young boy, taking it home and nursing it back to health, then releasing it. That event cemented his lifelong love for birds.

I feel wistful now that I didn’t make audio recordings or write down some of my mother’s stories.

I signed up for an online course, “From Autobiography to Illustrated Story.” The goal is to produce a short, illustrated book about an object that we still have from childhood: its provenance and meaning to us. I have precious few objects to choose from. The yellow Tonka truck. A doll my mother made for me out of an old sock with yarn hair and an embroidered mouth, nose, and eyes. Little Bear, the Steiff teddy. And I have some things that belonged to my mother.

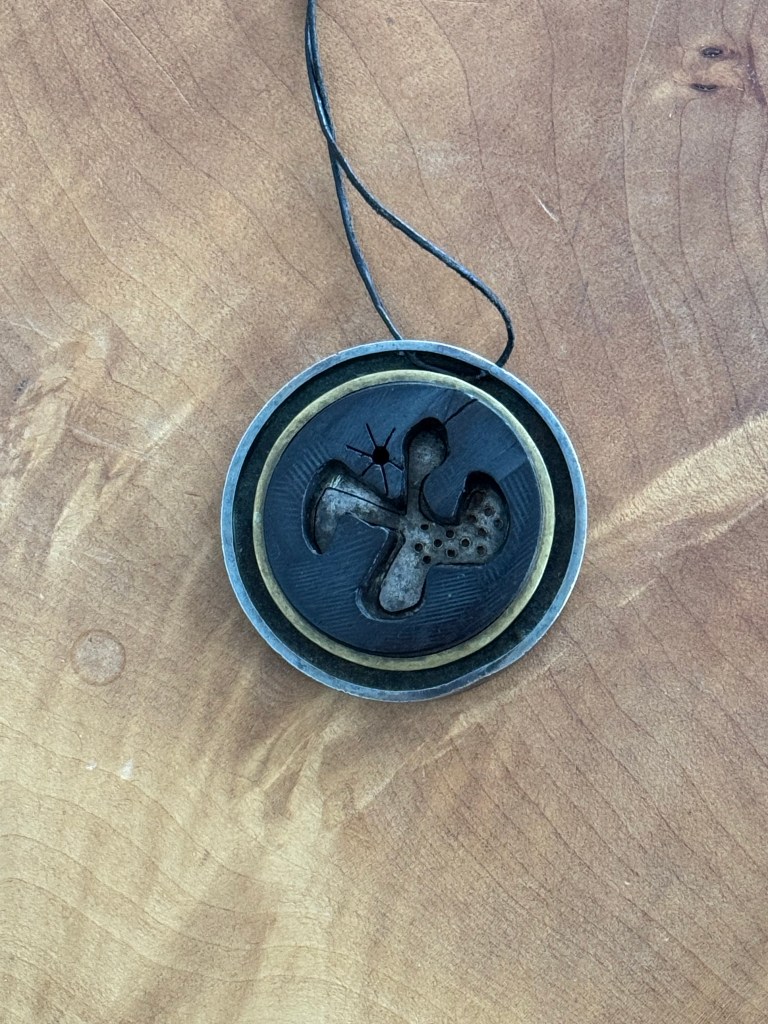

I decided I wanted to write about my mother’s Macchiarini pendant. My sister took it from her house after her death and gave it to me, thinking it suited me. I agree. Mom loved the work of Peter Macchiarini, an American Modernist jeweller (1909-2001) from North Beach, San Francisco. The several pieces my mother owned were passed down to us, her daughters. I have a couple of brooches, the pendant, and two belt buckles, and my sisters have other examples of his work.

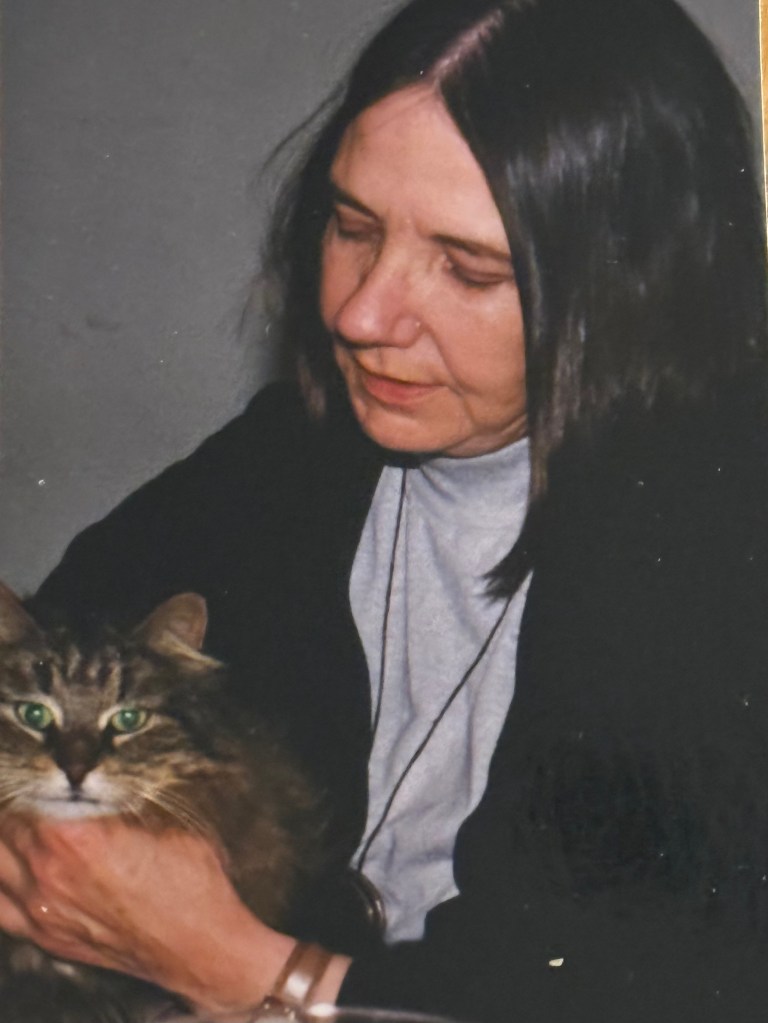

I want the pendant to tell a story—a story about my mother’s love for mid-century art, particularly from the Bay Area. Mom knew Peter, or at least I think she told me she did. She must have had anecdotes about how she bought the jewelry, what he was like, her San Francisco connection to him. She wore this pendant often, her signature piece. The photo of her and my dad shows her wearing it in 1964. She is wearing it again in the photo with her cat when she was in her sixties.

But the stories about Mom’s relationship with Macchiarini died with her. I can’t remember anything, and now I can’t ask her about them. What can I say about this unusual round pendant, a playful amoeba shape carved into dark wood and set in silver and gold? I can say that when I wear it, I feel warmth under its weight. Warmth around the heart, generated by affection. Our relationship was complicated. She was fucked up, inevitably passing along some of that to me. Yet there was so much love. She instilled in me a reverence for life’s beauty. And inextricable from that, a cellular knowledge of sadness.

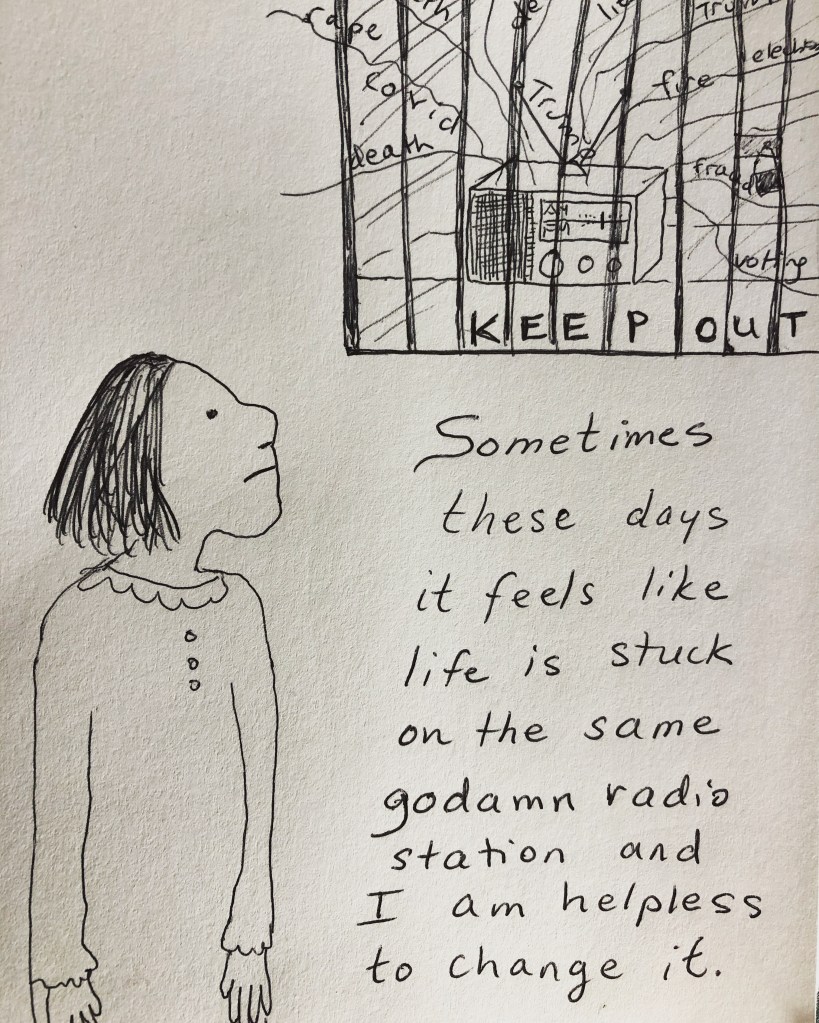

At the time, I thought the big change the Tower signified was the crumbling of ego. I was being called to surrender to the slow incremental losses of old age. But the Tower signifies sudden change, and today I believe it foretold the capital c Change the pandemic has brought: change that shakes the very foundations of our lives, change that brings our beliefs and systems under scrutiny and asks us what is most important in life.

At the time, I thought the big change the Tower signified was the crumbling of ego. I was being called to surrender to the slow incremental losses of old age. But the Tower signifies sudden change, and today I believe it foretold the capital c Change the pandemic has brought: change that shakes the very foundations of our lives, change that brings our beliefs and systems under scrutiny and asks us what is most important in life.

For Frankie

For Frankie