I work a volunteer shift at the upcycle store on Wednesdays. The people that come in delight me, entertain me, astonish me, educate me, soften me. Next week is my last shift at the store. I want to remember some of these people and their stories.

Once a pale man came in and asked if we had a leather hole punch. He didn’t want to buy one, just borrow it so that he could put an additional hole in his belt. He was losing weight, and his pants were hanging on him. Alas, I said, we don’t have one right now. I’m sorry.

I thought about him for weeks, his weight loss, his thinning frame, his sad face. I wondered about his story. Perhaps he was lovesick.

I can no longer untangle my hair

I feed on my own flesh in secret.

Do you want to measure how much I long for you?

Look at my belt, how loose it hangs.Anonymous, Six Dynasties

Translated from the Chinese by Kenneth Rexroth

As if to balance the sadness of the shrinking man, the joy of meeting Randy bloomed inside of me for weeks. He flounced into the store a few days before Thanksgiving, smelling gloriously of rosemary and thyme. Randy is a contemporary dandy, stained waistcoat and tight jeans, flowing grey hair, phlegmy smoker’s laugh lighting up his brown, creased face. He brought crackling energy into the store with him, along with a small plastic bag of herbs.

Do you have any Scrabble tiles? he asked. Yes, I handed him two tall mason jars filled with tiles, and as he dug through his pockets for the cash to pay for them, he told me there was always a few Scrabble boards set up on his coffee table. When my friends come over, he said, they add a word or two or three. We play a never-ending game and nobody keeps score.

What a mouth-watering smell! He opened the plastic bag for me to see the long sprigs of green. I picked them at the side of the road, he told me, just around the corner. The herbs were volunteer plants, free for anybody that wanted them. I need sage, I said, for the Thanksgiving turkey. Oh, he said, I think there was sage growing as well. We smiled and said our goodbyes. An hour later he was back with three sprigs of sage he had picked for me and my turkey.

When I asked a young fellow what he was planning to make with the feathers he was buying, he challenged me: Guess. A headdress? No, good guess, but I am making flies for fly fishing, something his dad taught him to do. He fishes for cutthroat trout under the Bay Bridge with a bunch of female fishers who’d turned him on to it. I never knew!

Last week, a woman came in and poked into the baskets of wool, humming a tune. I noticed her tone—it was strong and true. You have such a beautiful voice, I said. Why don’t you sing us something? Suddenly, gloriously, she burst into “I’m Called Little Buttercup,” from Gilbert and Sullivan’s HMS Pinafore. Her rich mezzo-soprano filled the store as she strutted down the aisles, outthrust chest, a beautiful dockside vendor in love with the captain. I and another shopper were the lucky audience, mesmerized by a performance delivered among stickers and glue, balls of wool, knitting needles, jars of coloured beads.

I love hearing about the celebrations people are planning. The woman in her thirties who bought armloads of artificial flowers and a bolt of pale pink draping fabric for the table. She and her siblings had been planning a surprise party for their mother’s sixtieth birthday. She keeps mentioning she’s turning sixty, as if reminding us, said the young woman. She’s worried we’ve forgotten. Little does she know what’s in store! I laughed with her, feeling mudita, imagining the pleasure and wonder of her mother on that day. Surprise!

Finally, I sold the white canvas tent that was propped in the corner for months. The tent is perfect for children to hide and play in, and a woman bought it for her grandchildren. I told her about the teddy bear’s picnic birthday party I’d thrown for my four-year-old so many Decembers ago. We had a play tent pitched in our living room, and the children and their stuffies enjoyed tea and cake. The woman became excited and touched my shoulder in thanks. What a great idea! I’ve got to do that for my grandson! Then she told me that one Christmas her mother-in-law opened the gift of a vibrator in front of the whole family. I wasn’t sure what prompted the story, but we had a good laugh. Teddy bear picnics and vibrators, all in one afternoon.

There’s a regular customer who brings her baby buggy into the store, speaking softly and playfully to her little boy as she shops. She buys bits of fabric, thread, and zippers. Last week, as she paid for her stuff and her baby chortled and tried to put his toes in his mouth in the buggy beside her, she ran her hand over the camel-brown smocked dress she wore and its complementary quilted vest. I made all of this from an old bedsheet, she said. At times like this, I thought, I wish I could whistle. A good long, low whistle to show my WOW in a visceral way. Instead, I shook my head: You are amazing! Queen of Upcycling!

One day I was emptying out the green donation boxes, pricing and sorting items. My hand fastened on something soft. A bit of plush grey fur, perhaps once the collar of a stylish coat. Wrapped in thin tissue paper, there was a small tag safety-pinned to the edge: Chinchilla, written in the shaky script of somebody very old. Suddenly, I was back in the furrier’s on Spadina Avenue, sitting cross-legged on the dusty floor, playing with scraps of chinchilla, beaver, spotted lynx. I caressed them one at a time, rubbed them against my cheek. My mother and the furrier stood above me, two voices discussing the racoon coat she’d ordered. What happened to that coat? And why was my mother—a passionate animal lover—buying a custom-made fur coat?

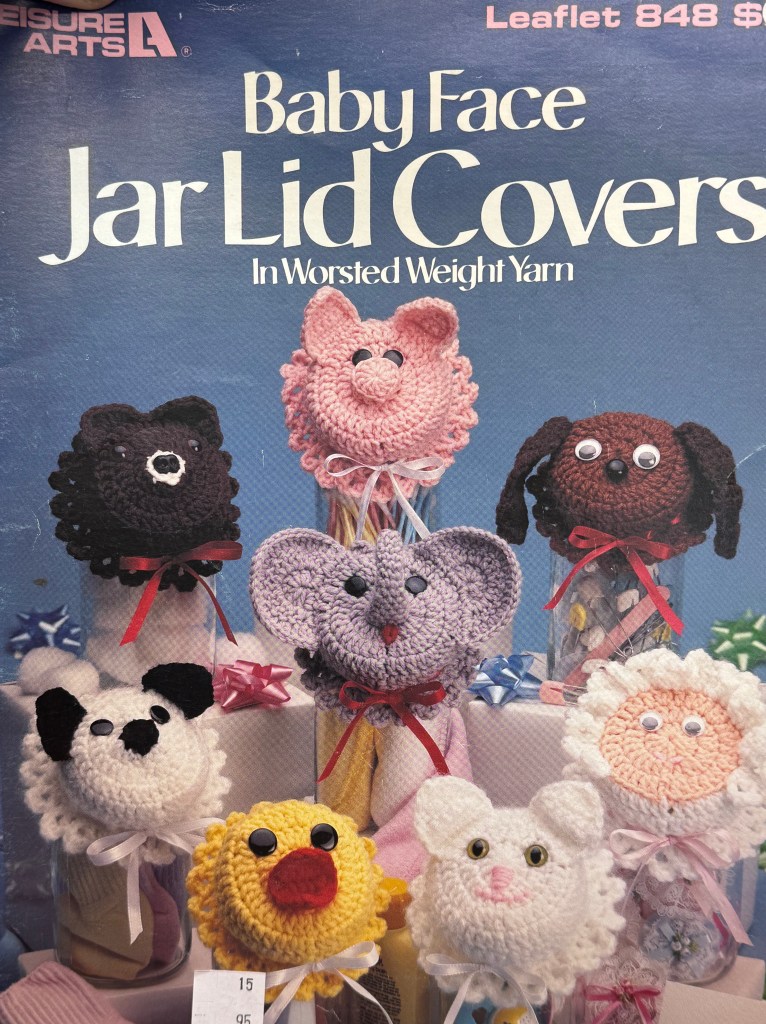

People stream into the store. Have you got books on stained glass? Do you have leatherwork tools? Ever get pillow inserts? Sometimes I say no, sometimes yes, but other times I’m not sure, and we set out to look together, sifting through the boxes and baskets. Sometimes people cry out in delight when they find just what they were looking for. A particular size of crochet hook, fabric printed with mushrooms, a colouring book of Frida Kahlo drawings.

Last week, a short bespectacled woman said she had an unusual request: golf balls. She was undergoing physiotherapy for an injured hand and the therapist had told her to squeeze a golf ball. I haven’t seen any golf balls, I said, but I think I can help. I remembered that morning finding a bag of large wooden beads strung onto a white shoelace. I thought of a small child or a very old person practicing fine motor skills, threading each bead onto the end of the lace. I found the bag and fished out three of the beads. They were about the size of golf balls. Will this do? I asked as I slipped them into her cupped hands. They’re perfect! And we agreed that they were much nicer to handle, a globe of burnished brown wood rather than a cold, plastic golf ball.

At the end of every shift, as I cash out, sweep the cement floor, turn off the heat and lights, lock the door, I feel full of the people I’ve met, the stories I’ve heard.

My favourite Arbutus tree was doing her usual backbend into the Colquitz River, her waxy leaves dipping into the brown flow. On my visit yesterday, I leaned into her, as I always do, feeling the cool papery bark under my bare arms and thighs. It’s dry, high summer, and the river is low and sludgy. I walk a little way down the path toward the water and crouch in a sunny spot surrounded by white umbrellas of Queen Anne’s Lace swaying in the slight breeze. The drone of bees. As I gaze at the river, a movement on the opposite bank catches my eye. A mother raccoon with four kits emerges from the undergrowth. The kits follow her lead and stand in the shallows, “washing” their paws in the brown liquid. A sound between a cat’s purr and bird-song chirrups from the large female as she guides the kits along the bank, batting one occasionally when it pauses too long in the water. The creatures disappear quickly back into the hedges and I am left watching the treacly river wend its lazy way.

My favourite Arbutus tree was doing her usual backbend into the Colquitz River, her waxy leaves dipping into the brown flow. On my visit yesterday, I leaned into her, as I always do, feeling the cool papery bark under my bare arms and thighs. It’s dry, high summer, and the river is low and sludgy. I walk a little way down the path toward the water and crouch in a sunny spot surrounded by white umbrellas of Queen Anne’s Lace swaying in the slight breeze. The drone of bees. As I gaze at the river, a movement on the opposite bank catches my eye. A mother raccoon with four kits emerges from the undergrowth. The kits follow her lead and stand in the shallows, “washing” their paws in the brown liquid. A sound between a cat’s purr and bird-song chirrups from the large female as she guides the kits along the bank, batting one occasionally when it pauses too long in the water. The creatures disappear quickly back into the hedges and I am left watching the treacly river wend its lazy way.

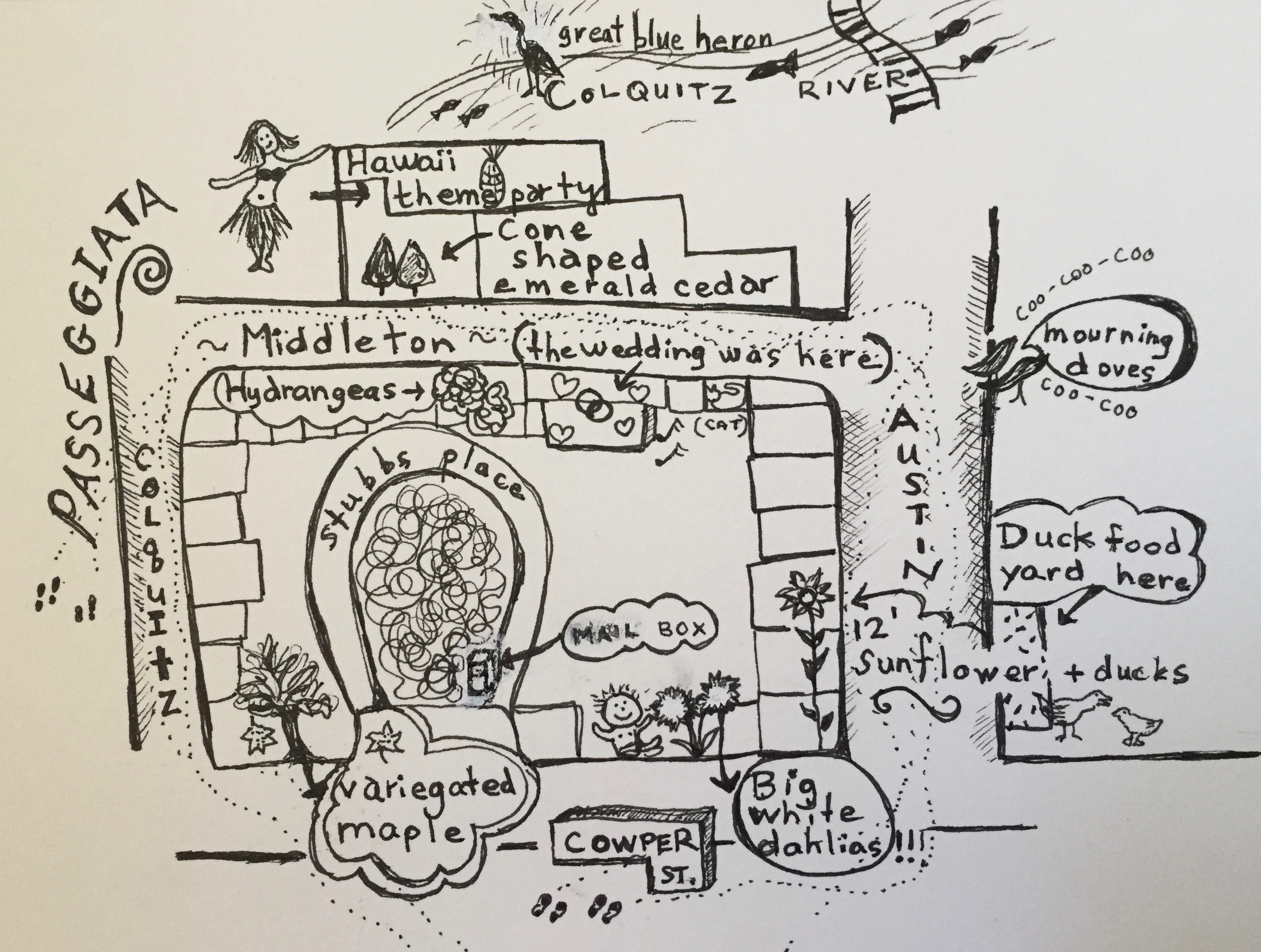

A passeggiata is the Italian tradition of a gentle stroll taken around the neighbourhood after dinner. It’s also a vital part of the “

A passeggiata is the Italian tradition of a gentle stroll taken around the neighbourhood after dinner. It’s also a vital part of the “