One autumn we went to visit my sister where she was cooking for a lodge in Cigarette Cove. Her partner ran the place and took visitors on fishing trips. We stayed for a few days, enjoying the remote location on the coast. The boys went fishing while I stayed with my sister in the warm kitchen, talking and laughing, catching up after months apart. I decided to make bread, but after all the preparation and long kneading, it didn’t rise. Disappointed, I threw the white blob atop a pile of food waste in a garbage can.

That night, we walked down the L-shaped dock to our rooms, the water lapping, the dogs running up and down among our legs, the moon laced with moving clouds. In the morning, we woke to the loons calling. When I went to make coffee in the big kitchen, the white blob had risen to a huge balloon of dough. My sister and I carefully removed it from the heap. I scraped off a few coffee grounds, punched it down, formed two loaves, let it rise again, and later that day we had the most delicious fresh bread for lunch.

My sister and I sometimes laugh about the legendary “garbage bread.” I love the slow riser, the late bloomer. The way that stories and bread and flowers surprise you when you least expect it. The way that people grow yeasty and bloomy in their late years, amazing us by finally doing what makes their hearts sing.

So I don’t need to rush the stories. Forget about the goal to have ten written by Christmas. Why? I can let go of the expectations that academia trained in me: Always write to a deadline. Keep sending stuff out. Succumb to the pressure to publish. I don’t need to operate on that schedule. I can slow cook stories for months, if I want. Who cares?

These last few weeks I have been dipping into short stories by Raymond Carver (Where I’m Calling From) and Sharon Butala (Fever), two very different authors who do not satisfy. They leave me yearning and wondering. And yet in the wanting, there is such pleasure. They make me realize that I can let go of my need to have “closure” or to “wrap up” my narratives. I was reminded of this as well when I saw more than one student in the Writing Centre this week asking for help in understanding Alice Munro’s “Gravel.” Wondering, feeling, not knowing—this is what stories by all three of these writers engender in me.

From a story I am cooking now: The swimming pool came in and out of my shifting vision. White lights shimmered up through the blue water. The rest of the yard was in shadow. “Guys, c’mon,” I whispered behind me as we all scaled the concrete blocks like monkeys. Soft rock played through the open verandah door. “We’re going to get caught,” I said to the boys ascending behind me. And then suddenly I went over with a thud and red pain on the other side.

The boys leapt over to help me, saw the weird tilde of my white arm against the black grass. “Shit she broke it, I can tell by the swerve of it, look.” The other boy felt my arm near the elbow and I cried out in pain.

The soft rock clicked off and we heard clip clop steps from the pool deck. The walker was wearing heels. “What the hell is going on over here?” came a woman’s shrill voice. Soon she came flapping over to our huddle in a diaphanous gown, her perfumed head dunking into our circle of bodies. “You kids are trespassing, I should call the cops,” she cried again, trying to rouse the boys to lift their shaggy heads to look into her eyes. One of them, Pete, said, “Sorry, ma’am, but our friend has a broken arm. Can you call the ambulance, please?” Pete labored at enunciation, trying to pull up the sloppy vowels so he didn’t seem so wasted.

I was met at the hospital by my mother, who sat with me on a hard wooden bench in the hallway. “How could you be drinking? You’re under-aged. Like way under-aged! You’re 13, for god’s sake! Where the hell did you even get the booze? Who booted for you? I’ll wring their necks, the fuckers,” she spit-whispered into my ear. The crisp nurses clucked their disapproval as they passed. “No painkillers for you until the alcohol is out of your system,” said one when I groaned in agony. I was being punished. I could see it in their amused, accusing eyes.

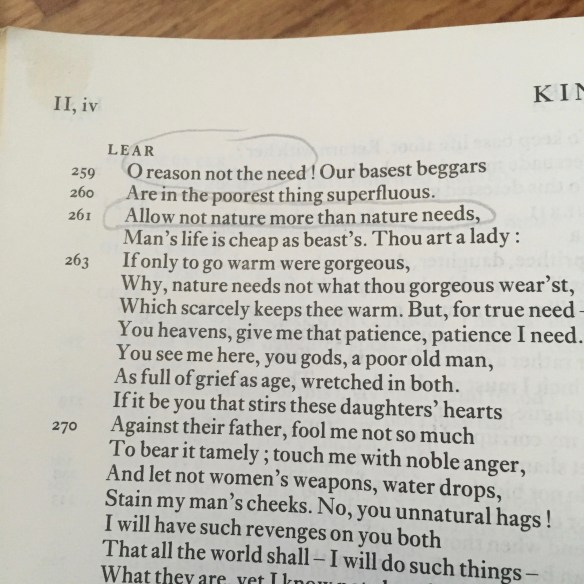

I do not know what to do, exactly (see Barthelme), but I know that limiting myself to writing only what I know is the equivalent of Goneril and Reagan’s telling their father, you don’t really need all that finery, that retinue. I join Lear in saying, “reason not the need.” Let me read, research, imagine. Let me grab from a cornucopia of ideas, thoughts, books, facts, art, beauty, and experiences to make stories. Here I go into story number eight. I’ll report back later.

I do not know what to do, exactly (see Barthelme), but I know that limiting myself to writing only what I know is the equivalent of Goneril and Reagan’s telling their father, you don’t really need all that finery, that retinue. I join Lear in saying, “reason not the need.” Let me read, research, imagine. Let me grab from a cornucopia of ideas, thoughts, books, facts, art, beauty, and experiences to make stories. Here I go into story number eight. I’ll report back later.

The blog, however, will be more erratic.

The blog, however, will be more erratic.