I’ve devoured most of Anne Tyler’s novels in the last two years. It was one of those felicitous discoveries—a wonderful, prolific novelist I hadn’t read yet. Yes, I’d heard the title The Accidental Tourist, but it wasn’t until I found Breathing Lessons in a little free library on Brunswick Avenue, Toronto, a couple of summers ago, that I became engaged, in love with her characters, the messy lives, flawed people and relationships, random and serendipitous comings-together, the tenderness, the realness, the love. I was hooked. I read all of the novels available from the library and bought a couple that weren’t, and then, just a few weeks ago, I found Ladder of Years in a box of free books across the street. What a find! Read this:

“When my first wife was dying, . . . I used to sit by her bed and I thought, This is her true face. It was all hollowed and sharpened. In her youth she’d been very pretty, but now I saw that her younger face had been just a kind of rough draft. Old age was the completed form, the final, finished version she’d been aiming at from the start. The real thing at last! I thought, and I can’t tell you how that notion colored things for me from then on. Attractive young people saw on the street looked so. . . temporary. I asked myself why they bothered dolling up. Didn’t they understand where they were headed? But nobody ever does, it seems.”

From Ladder of Years by Anne Tyler

I was disarmed by that paragraph. My perspective about my aging face swiveled to a fresh view: the temporary beauty of my youth was just a rough draft. This idea appeals to me not just because it helps me consider my face as closing in on the finished version, the real thing. It’s also because I work with writers, and I see lots of rough drafts, and I found the metaphor very appealing. Not only are our lives works-in-progress—our faces are also works-in-progress. The changes I see in mine are not to be read as signs of deterioration; they are signs of me becoming more me.

I am also reading Stranger in a Strange Land, by Robert Heinlein. Years ago, when Michael first used the verb “grok,” I asked him what it meant, and he told me about Heinlein’s science fiction classic. I’m finally reading it, discovering a new world, new words: grok (to fully understand, become one with), discorporate (to die), and water brother (someone you shared a drink of water with, which binds you together).

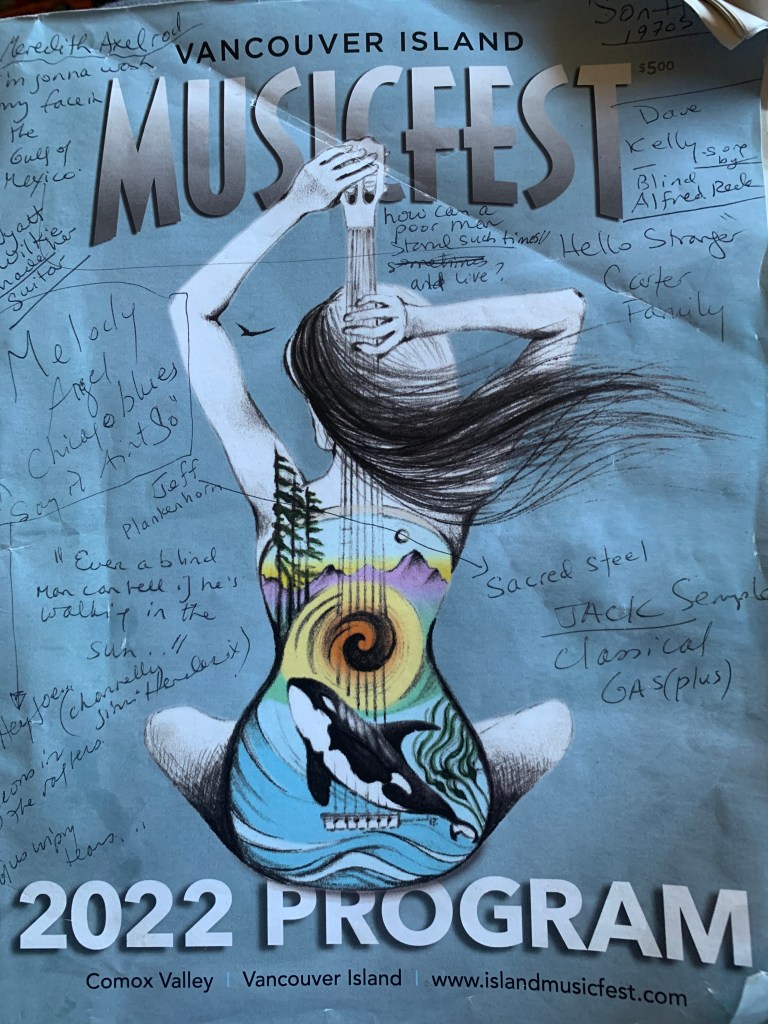

Valentine Michael Smith (the Martian in the novel) would have loved Vancouver Island Musicfest, teeming with water brothers. We were there last week-end, and still, I am digesting the banquet that it was. On Saturday morning, we found seats in the barn, one of the small stage venues. The place smelled of horses, and the was air thick with hay particles. On the stage, the musicians settled with their instruments—soundchecks, noodling. This was our first time hearing live music for a while—and I sat upright with anticipation. The workshop was well-titled “Great Guitars,” and soon I was swept into the greatness of a bunch of highly skilled and talented guitarists playing, singing, and sometimes jamming.

Meredith Axelrod, who blushed beet red when she got a name wrong, sang an old Carter Family song called “Hello Stranger”: “Hello, stranger, put your loving hand in mine/ Hello, stranger, put your loving hand in mine/ You are a stranger and you’re a pal of mine.” Her charming manner and amber voice were a tonic to start the show. Her second song featured the line, “I’m gon’ wash my face in the Gulf of Mexico.” She rose, raised her jean-clad leg, and set one foot on her chair, cradling her glowing Wyatt Wilkie guitar. I liked her old-timey manner and voice. I imagined her scooping salt-warm water from the Gulf and splashing it over her face between blonde wings of hair.

I liked everyone on the stage. Jeff Plankenhorn, wearing his special “Plank” cross between a lap steel guitar and an electric guitar, sang that even a blind man can tell if he’s walking in the sun. Jack Semple was there, showing off with his masterful classical gas. Dave Kelly reminded me of Clapton with his British accent and easy elegance. He played a Son House blues tune as a pigeon flew up into the rafters. Then there were the old guys at the back of the stage who—not needing to be seen or noticed—had tucked their egos into the back pockets of their jeans. They picked away, nodding and tapping, studying their instruments, heads down. Music has its own rewards.

The star of the show was Melody Angel, guitarist and singer from the south side of Chicago. When she sang “Hey Joe,” Michael leaned over and said, “I think she’s channelling Jimi.” Her muscular voice growled up over the crowd, and we pulsed along with her guitar. She pushed notes up the ladder of sound, climbing, climbing, raising our energy. Michael’s lit-up face was plastered with a beautiful smile, and he wiped a tear from his eye. My throat was thick with emotion as I looked around at the performers and the audience, all of us gathering to grok this powerful medium of music, the great connector, the universal love potion. As we clapped and clapped some more, I was filled with sound, in love with the world

In the summer of 2011, Michael and I bought tickets to the Edmonton Folk Festival. We knew we were taking a chance—we’d met only two months earlier, and to spend so much time together was a quick, risky test of our compatibility. We drove through the mountains, stopping at cheap hotels and laughing a lot.

On the way, I got schooled in the songs of Stephen Fearing, and then we listened to Captain Fantastic and the Brown Dirt Cowboy—the whole album—loud. I’d never really heard Elton John until that day. At the festival, we swooned over Matt Anderson and Taj Mahal and got closer and closer to each other. Our love was just a rough draft then, and the music we shared on the way to Edmonton and at the festival was like the first version you write—filled with exploration. The discovery draft, we call it at the Writing Centre. More than a decade passed. And last week-end, at another music festival, we added some nice touches to the current draft. We shared music, and that’s like co-writing a paragraph. We move slowly, inexorably toward the final, finished version, becoming more ourselves each day.

A few weeks ago, I picked up Octavia Butler’s The Parable of the Sower from the cute little library on the front yard of a house around the corner. “Take a Book, Leave a Book” was painted in curlicued white letters across the blue cupboard doors. When I was a teenager, I decided I wasn’t interested in science fiction. Somehow, I only wanted to read things that were “real.” So I turned to 19th century British novels and early-mid 20th century American writers like Philip Roth and Saul Bellow. Of course I have cast my reading net much wider since then, but I still don’t tend to be drawn to science fiction or its sister genres, fantasy and horror. Yet, as I dug into Butler’s novel, I became engrossed by the young female narrator/ protagonist Lauren who is bent on survival in a dystopian America of the future. Her warrior spirit drives her to escape from the murder of her family and razing of her home in a gated community in Southern California and form a motley tribe of people all searching for safety. Due to her mother’s drug abuse, Lauren was born with hyperempathy, a disability that has her feeling other people’s pain to a debilitating degree. She develops a religion called Earthseed, whose God is Change because the only thing we can be certain of is that everything changes. What felt eerie about this novel, written in 1993, was that Butler’s portrayal of a dystopian nation read as strongly resembling Trump’s America.

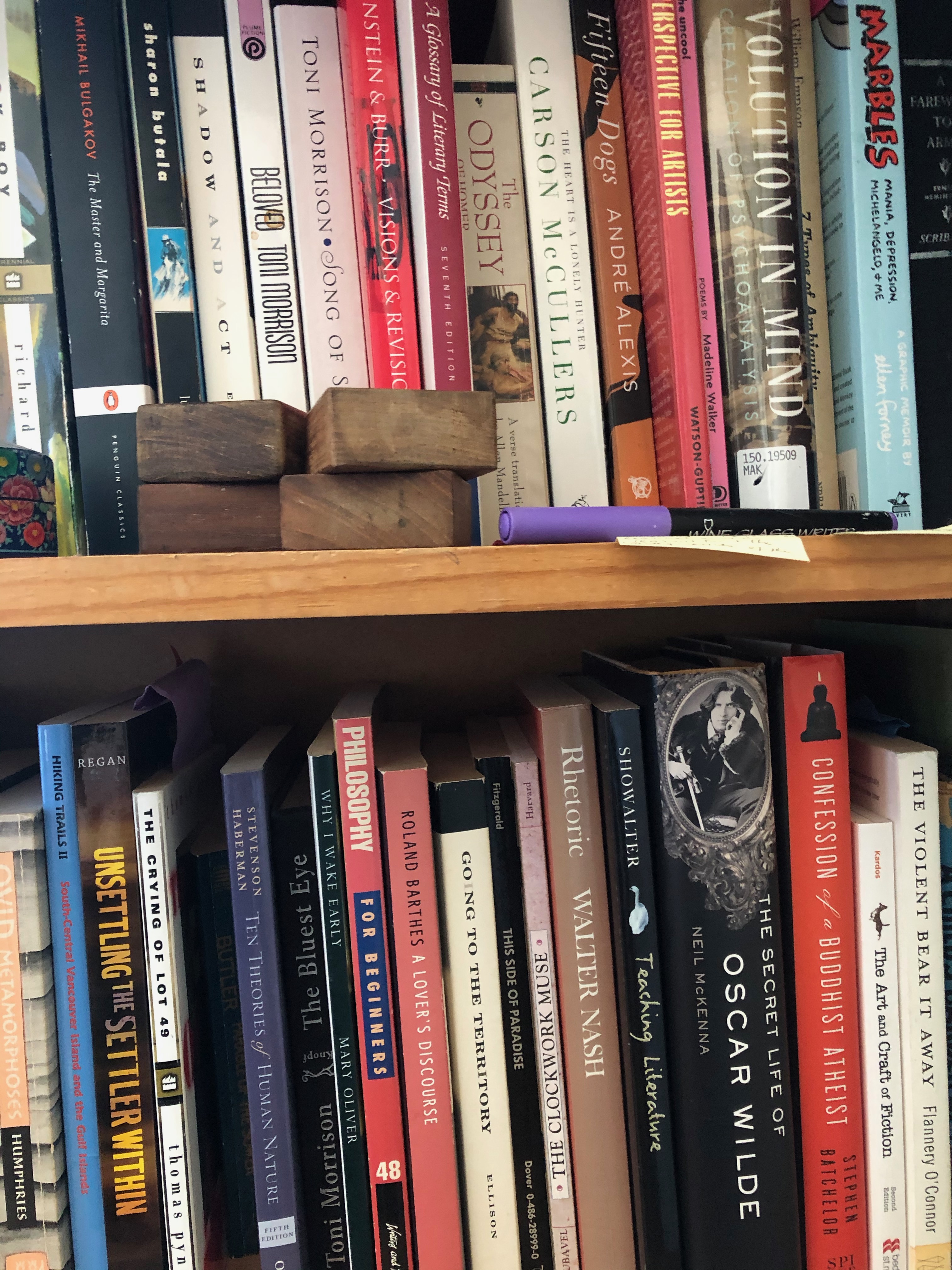

A few weeks ago, I picked up Octavia Butler’s The Parable of the Sower from the cute little library on the front yard of a house around the corner. “Take a Book, Leave a Book” was painted in curlicued white letters across the blue cupboard doors. When I was a teenager, I decided I wasn’t interested in science fiction. Somehow, I only wanted to read things that were “real.” So I turned to 19th century British novels and early-mid 20th century American writers like Philip Roth and Saul Bellow. Of course I have cast my reading net much wider since then, but I still don’t tend to be drawn to science fiction or its sister genres, fantasy and horror. Yet, as I dug into Butler’s novel, I became engrossed by the young female narrator/ protagonist Lauren who is bent on survival in a dystopian America of the future. Her warrior spirit drives her to escape from the murder of her family and razing of her home in a gated community in Southern California and form a motley tribe of people all searching for safety. Due to her mother’s drug abuse, Lauren was born with hyperempathy, a disability that has her feeling other people’s pain to a debilitating degree. She develops a religion called Earthseed, whose God is Change because the only thing we can be certain of is that everything changes. What felt eerie about this novel, written in 1993, was that Butler’s portrayal of a dystopian nation read as strongly resembling Trump’s America. I always prefer books as objects over digitized texts. I love the feel and look of books. I love to explore marginalia and marks, run my hands over bindings, examine tatters and pages folded over, text that has been underlined. The other day I picked up a well worn novel (The Lotus Eaters by Tatjana Soli) from a free library that had written in the inside cover in elegant cursive, “Property of” followed by a rectangular stamp: The Cavern Hotel and Café, El Nido, Palawan. I Googled this mysterious place and discovered it is a hotel offering pod accommodations in the Philippines. So interesting. (The next day, Trip Advisor wondered if I would like to see the current rates for staying the Cavern.)

I always prefer books as objects over digitized texts. I love the feel and look of books. I love to explore marginalia and marks, run my hands over bindings, examine tatters and pages folded over, text that has been underlined. The other day I picked up a well worn novel (The Lotus Eaters by Tatjana Soli) from a free library that had written in the inside cover in elegant cursive, “Property of” followed by a rectangular stamp: The Cavern Hotel and Café, El Nido, Palawan. I Googled this mysterious place and discovered it is a hotel offering pod accommodations in the Philippines. So interesting. (The next day, Trip Advisor wondered if I would like to see the current rates for staying the Cavern.) the dark, I enter into the world of Butler’s novel, where kindness is the last good thing, where people band together in tribes because love and human relationships are all that we have, and where impermanence is the only truth. Wait a minute, all of that is sounding familiar. Is it really the future, or is it now?

the dark, I enter into the world of Butler’s novel, where kindness is the last good thing, where people band together in tribes because love and human relationships are all that we have, and where impermanence is the only truth. Wait a minute, all of that is sounding familiar. Is it really the future, or is it now?

At the time, I thought the big change the Tower signified was the crumbling of ego. I was being called to surrender to the slow incremental losses of old age. But the Tower signifies sudden change, and today I believe it foretold the capital c Change the pandemic has brought: change that shakes the very foundations of our lives, change that brings our beliefs and systems under scrutiny and asks us what is most important in life.

At the time, I thought the big change the Tower signified was the crumbling of ego. I was being called to surrender to the slow incremental losses of old age. But the Tower signifies sudden change, and today I believe it foretold the capital c Change the pandemic has brought: change that shakes the very foundations of our lives, change that brings our beliefs and systems under scrutiny and asks us what is most important in life.