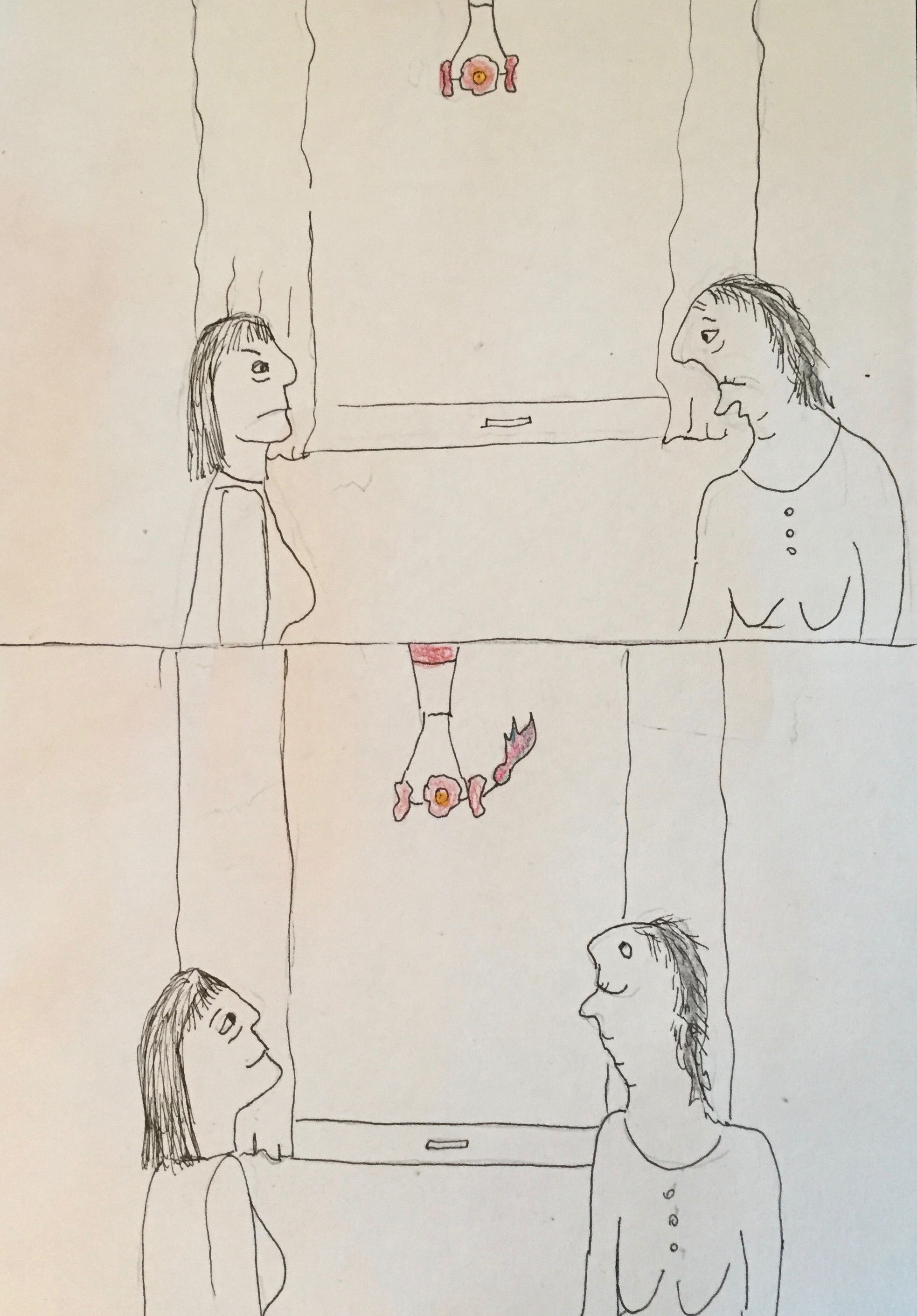

I angle my chair so I can see the hummingbird at the feeder, only a couple of feet away. Coat of metallic green feathers, needle beak, vibrating wings—an Anna’s hummingbird, so close I could touch her. She trembles as she drinks long and hard at the sugar water I prepared. A ping of pleasure as I watch her become nourished, sated.

When we moved into this house, June 2024, I decided not to put up a hummingbird feeder. Too much work, too much anxiety. I remembered that icy winter a few years ago, when I fretted over the birds getting their food. Once you commit to a feeder, you need to keep it going through the cold months. Non-migratory hummingbirds depend on nectar in feeders for sustenance. So, that January, when the temps dropped below freezing and the liquid in the beaker froze into solid chunks, I cut the toes off a pair of old wool socks and pulled them, one over the other, to encase the container of sugar water, trying to keep it liquid. Several times a day, I removed the feeder from its hook, brought it inside, and melted the ice, so the birds had access to food that was precious, rare, and necessary. I felt guilty when I let the liquid freeze for too long. Worried for days, until the cold spell broke.

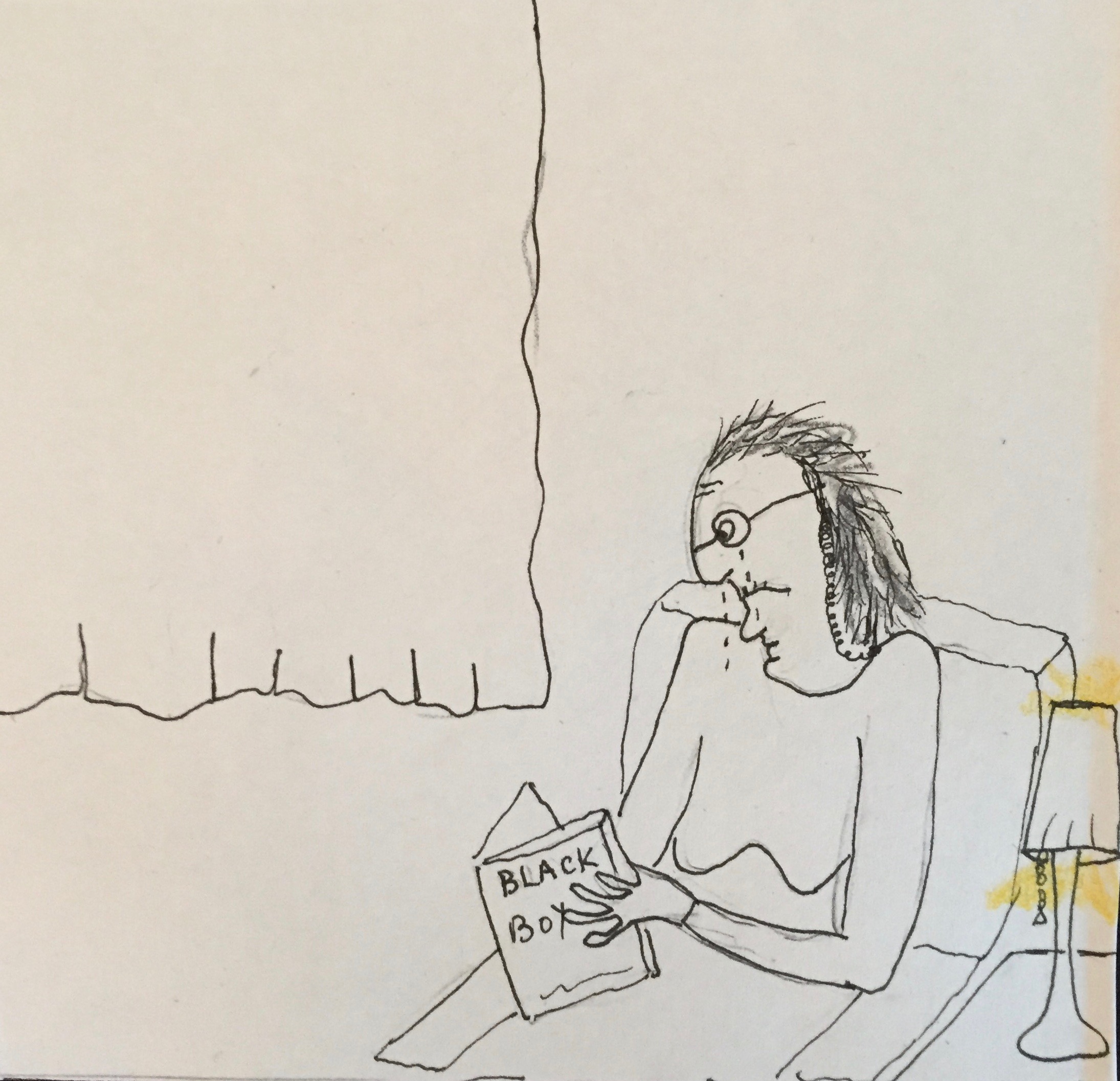

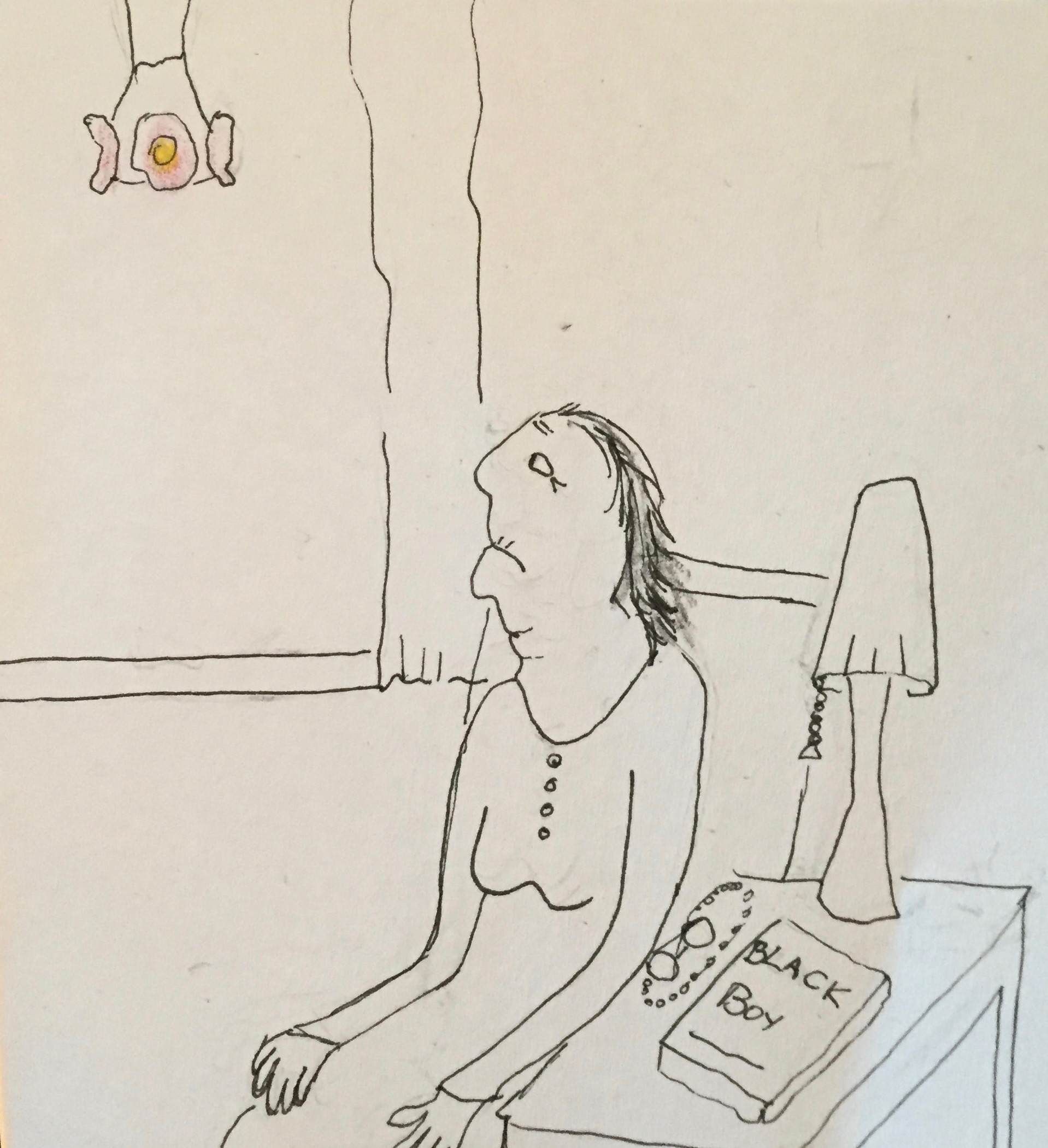

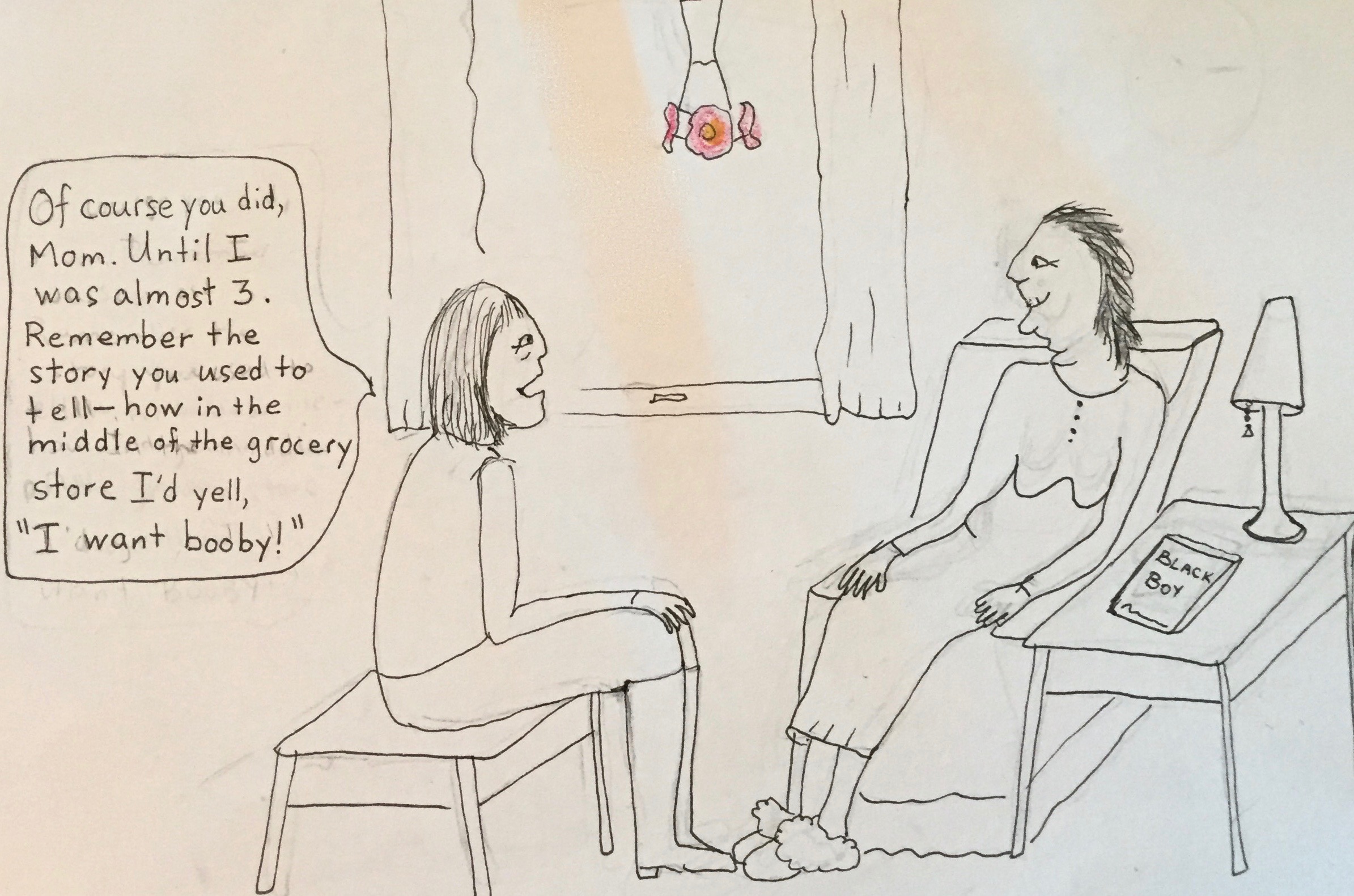

Save yourself the grief, I thought. Don’t put out a feeder again. Too much trouble. Yet, I didn’t get rid of the feeder with its four plastic red flowers. I must have known I would want it again someday. Yesterday, I dug it out from the back of a cupboard and made the nectar, 2 cups water, ½ cup white sugar. I was yearning for connection. I watched the first bird discover it hanging off the balcony rail, drawn by the gaudy red. As he fed hungrily, my body responded as if I were nursing a newborn again. Tiny being of my flesh, cradled close, skin on skin, painful tickle of let-down followed by a strong rush of milk, sustained by baby’s rhythmic sucking.

My body remembers well the flow of oxytocin, the pleasure, the sense of deep, silent connection with my sons. For eight years I breastfed three babies. Cellular memory.

Perhaps the sweet ping I feel when I watch a hummer drink its fill at the feeder can replace the rewards I look for on my smartphone. A few days ago, alarmed by how frequently I pick up the phone (for example, 21 pickups in 3 hours), I found a book I’d read in 2018 when it first came out. Catherine Price wrote How to Break Up With Your Phone (there’s a 2025 edition) because she saw how smartphones were grabbing our attention and changing our brains and our lives. I was concerned then, and I went through her 30 day “break up,” becoming by the end, more conscious and intentional when I used my phone. That worked…for a while. Fast forward to late 2025, and I’m back where I was but even worse.

I know it’s worse because when I attempted a digital “sabbath”—turning off the phone for 24 hours—I woke in the middle of the night, anxiety flooding my body, terrified of being cut off from life, from everybody I know. A great black wall towered between me and the living world. Existential loneliness. I crept out to the kitchen and turned the phone back on. Even though there were no texts, only junk emails, a whoosh of relief. A conduit had been re-opened. The potential for connection.

I know that my brain and body have been altered through smartphone use. Over the years, I notice decreased ability to read complex material for longer than a few minutes. I am highly distractible, grabbing my phone for no particular reason. Life feels fragmented. So, again, I plan to work slowly through Catherine Price’s 30 day break-up. I’ve quit other addictions: alcohol, cigarettes. I can do this.

Maybe when I feel the urge to grab my phone, I’ll head over to the feeder. Sit a while. Watch. Because observing hummingbirds at the feeder soothes me, reminds me of feeding my babies, sustaining them with my bountiful milk. The body’s sagacity. A promise to keep these little birds fed throughout the winter is part of the circle of commitment, connection, love, pleasure.

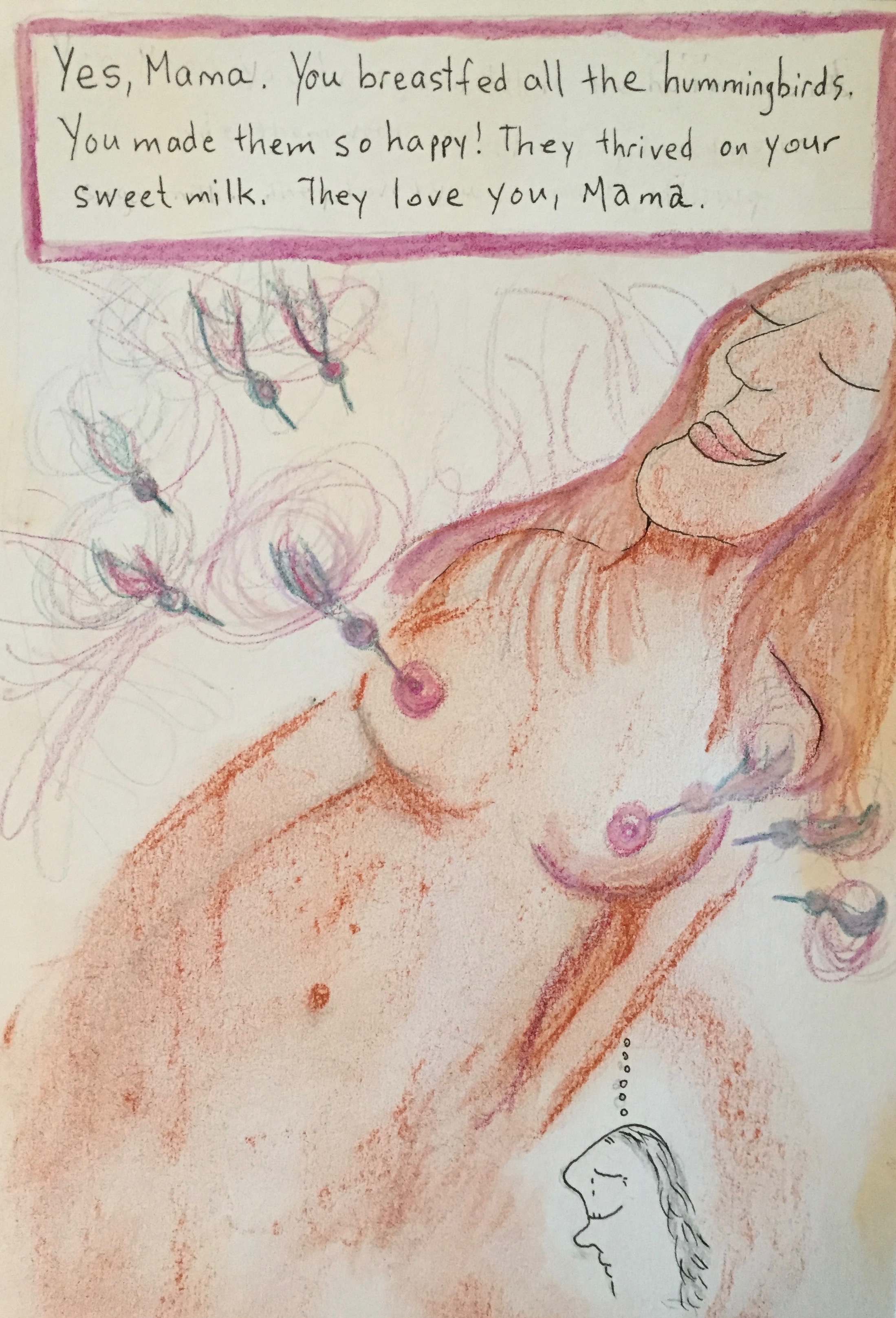

P.S. I made a weird comic about breastfeeding hummingbirds in 2017; clearly, I’ve been feeling this connection between hummers and nursing for a long time! I published it here: https://maddyruthwalker.com/2017/11/02/sweet-milk-for-the-hummingbirds/

Thanks for reading.

Thanks for reading.