Sometimes a word rolls around in my mind for weeks. Lately, it’s “shed,” both noun and verb. I started to make notes about “shed” and its associations. When I saw the document file that I’d titled “The Word Shed,” I recognized a new meaning: my mind is a word shed. A space where I collect words, play with them, combine them, examine their denotations and connotations, milk their honey.

Shed the noun is a simple roofed structure, typically made of wood or metal, used as a storage space, a shelter for animals, or a workshop: a bicycle shed | a garden shed | a woodshed. Or a place to work. Last summer we met a couple at their yard sale, and they showed us the woman’s “She Shed” in the backyard. They’d built the small one-room shed during the pandemic: it was a place for her to work at home in peace and quiet. I’d never heard the term “She Shed” before. I like it better than “Man Cave.”

The Shed is a restaurant in Tofino where, two years ago on my sister’s birthday, I had a delicious salmon bowl that I recreated at home later. I knew the ingredients: salmon, quinoa, raisins, almonds, chopped apple, kale, white cheddar. I intuited a dressing of tahini, olive oil, lemon juice, garlic, honey, and yogurt. I discovered the recipe, handwritten on blue paper, in my recipe binder and realized that I’d somehow cared enough to reverse engineer the recipe, though I can’t remember writing it down.

I made the Salmon-Kale-Quinoa Bowl again the other night and it was delicious. I didn’t have white cheddar or puffed rice, so I used shaved parmesan and skipped the puffed rice.

The Shed restaurant invokes a homey feel. I remember being there with Jude and Michael, tucked into a cozy booth while rain spattered the windows and wind whistled outside. Like sitting in a warm shed on a stormy day. We walked on the beach after lunch in our rain gear.

Over the years, we’ve had two sheds built on our property for storage, bicycles, and garden stuff. Now we’re moving and clearing out the sheds. I’d forgotten about the stuff I stored there. Out of sight, out of mind were boxes of old letters, some going back forty years; kids’ artwork, writings, and report cards; notes from university courses; my old journals. Sorting and shedding and shredding old papers over the last few months has been part pain, part joy, and sometimes so funny I laughed out loud.

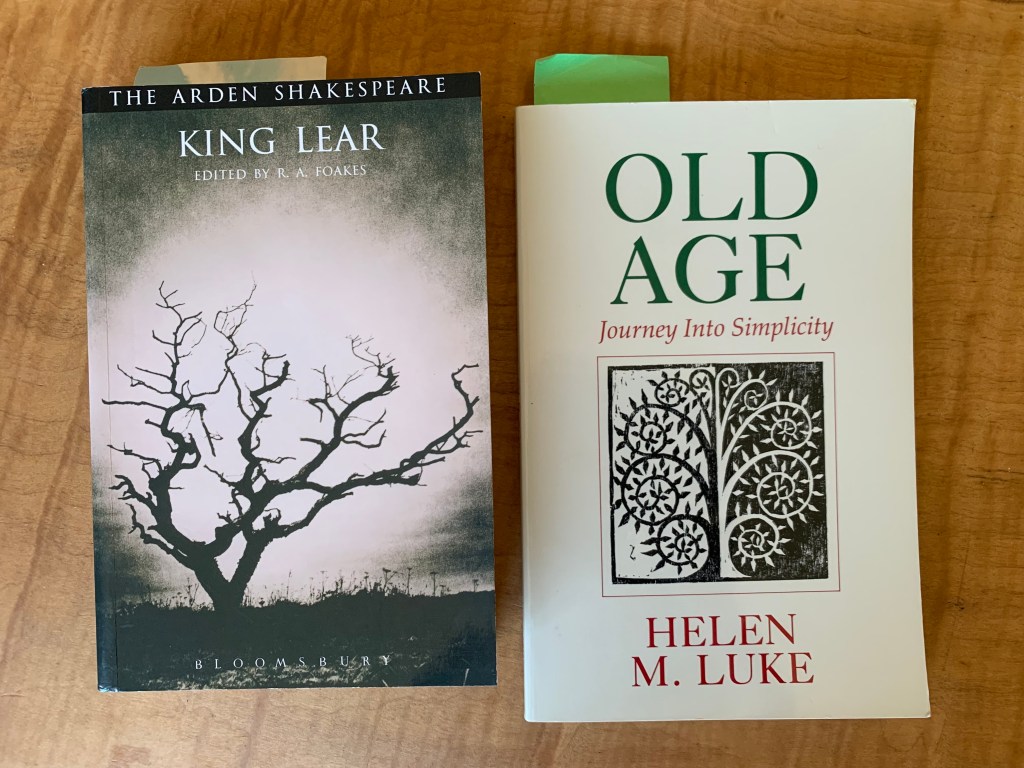

Another shed: On December 1, we’ll be in New York City to see Kenneth Branagh in the role of King Lear at the Shed, “a new cultural institution of and for the 21st century.” Their website explains: “We produce and welcome innovative art and ideas, across all forms of creativity, to build a shared understanding of our rapidly changing world and a more equitable society.” After a run in London, England, Branagh is bringing the play to this exclusive U.S. engagement.

It’s months away, but of course we had to buy tickets early. It will be exciting to see Branagh play Lear in my favourite Shakespeare play. I am reading Helen Luke’s book Old Age, and the chapter on King Lear moved me, particularly when she refers to the two lines spoken by Lear to Cordelia in Act 5, Scene 3, “When thou dost ask me blessing I’ll kneel down / And ask of thee forgiveness.” Luke writes,

“If an old person does not feel his need to be forgiven by the young, he or she certainly has not grown into age, but merely fallen into it, and his or her ‘blessing’ would be worth nothing. The lines convey with the utmost brevity and power the truth that the blessing that the old may pass on to the young springs only out of that humility that is the fruit of wholeness, the humility that knows how to kneel, how to ask forgiveness” (p. 27).

Lear’s story resonates because he shows us that shedding egotism and pride may be followed by an exquisite sense of humility. Many of us experience this as we grow older. Only after Lear is hollowed out by loss can he enjoin Cordelia to “live / And pray, and sing, and tell old tales, and laugh / At gilded butterflies.” Only after loss decimates us, do we feel an unusual lightness of being. So different from the lightness of youth, this lightness we purchase with grief.

Then there’s the verb, “to shed.”

To rid oneself of superfluous or unwanted things or feelings…to give off, discharge, or expel, such as a cat shedding fur, a snake shedding skin, a tree shedding leaves.

Shedding blood. Bloodshed. Viral shedding. We all shed tears.

And don’t forget the intransitive verb, to woodshed: to practice a musical instrument, to work out jazz stylings, to go over difficult passages in a private place where you can’t be heard.

Isn’t it odd that the noun shed refers to a place where you store and keep and gather things, whereas the action word (transitive verb) means to let go of, release, slough off feelings, body parts, objects? These meanings are in tension with each other – one wants to keep, the other to release.

But perhaps it isn’t so odd. The tension between the noun and the verb merely replicates the push and pull we feel in our lives between holding close and letting go.

The Shed in Tofino: https://www.shedtofino.com

The Shed in Manhattan: https://www.theshed.org/program/302-kenneth-branagh-in-king-lear-by-william-shakespeare

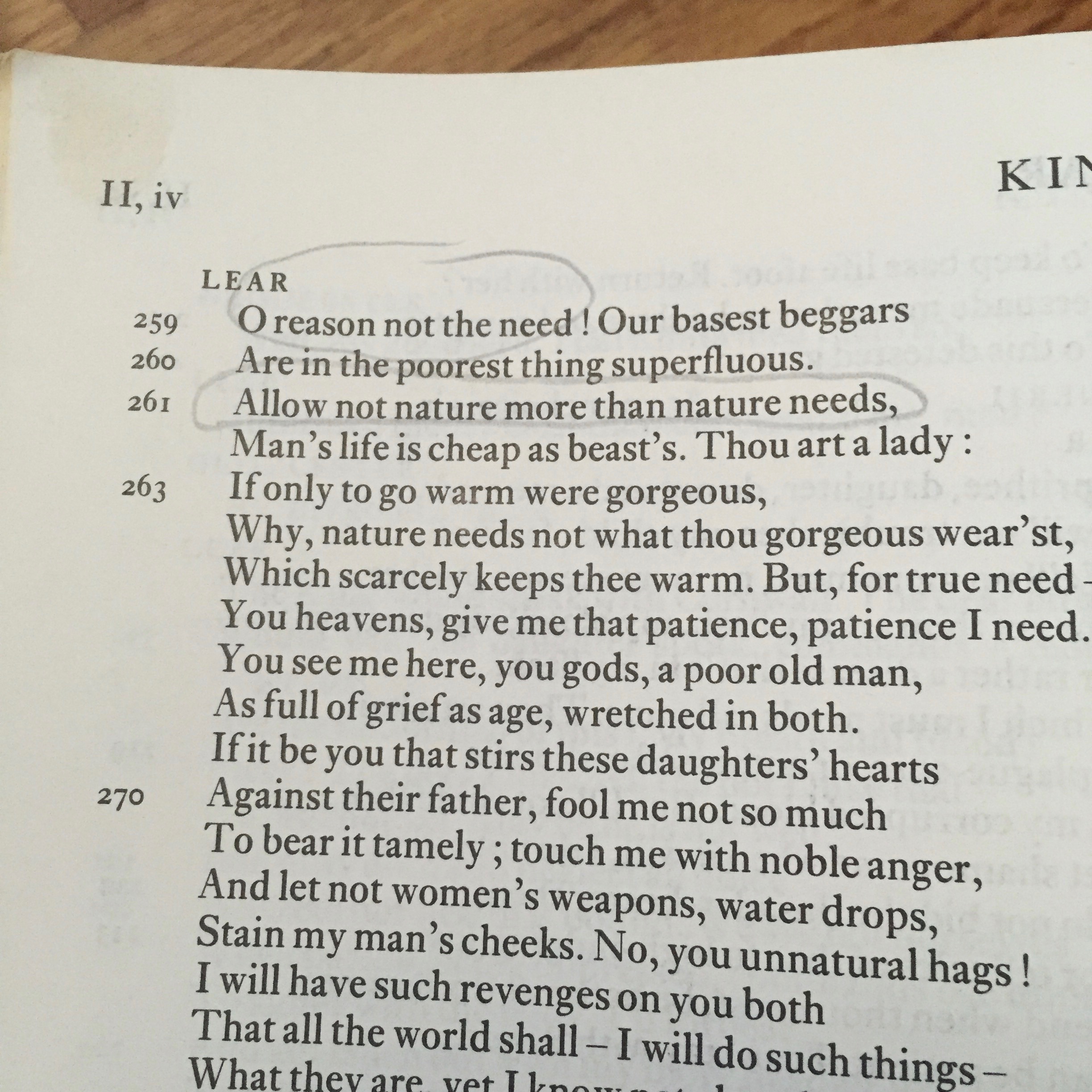

I do not know what to do, exactly (see Barthelme), but I know that limiting myself to writing only what I know is the equivalent of Goneril and Reagan’s telling their father, you don’t really need all that finery, that retinue. I join Lear in saying, “reason not the need.” Let me read, research, imagine. Let me grab from a cornucopia of ideas, thoughts, books, facts, art, beauty, and experiences to make stories. Here I go into story number eight. I’ll report back later.

I do not know what to do, exactly (see Barthelme), but I know that limiting myself to writing only what I know is the equivalent of Goneril and Reagan’s telling their father, you don’t really need all that finery, that retinue. I join Lear in saying, “reason not the need.” Let me read, research, imagine. Let me grab from a cornucopia of ideas, thoughts, books, facts, art, beauty, and experiences to make stories. Here I go into story number eight. I’ll report back later.