I am in Toronto for a few days. This city was my home from 1965 to 1989.

I have been walking Bloor Street West. First, the Mink Mile, that stretch between Yonge and Avenue Road lined with the tall glass storefronts: Zara, Birks, Lululemon, Holt Renfrew. Rich people shop here. Very few birds fly above these tall, inhospitable stores. Instead, big bird shapes in bright shiny colours line the sidewalks, ghosts of extinct species.

It’s cold in Toronto for late May. I wear a toque, jacket, leather gloves. But now I wish I’d brought a scarf. I admire the scarves in the window of Black Goat Cashmere, next to Ashley’s in what used to be called the Colonnade. This mall was one of my mother’s favourite places; after window shopping Bloor Street arm in arm, we’d drink coffee and eat pastries at the Coffee Mill at the back of the Colonnade.

I enter the store. Two saleswomen are upon me immediately. I ask about the small scarves, lifting one of them up out of the wooden box where they are displayed like confectionary, soft cashmere in artful designs, wool watercolours. “How much are these little ones?” “Oh,” says one of the women, advancing, “the Carre scarves are $385.” I laugh, folding the luxury item back into its box. “Perhaps in another lifetime.”

Pulling my zipper up to my chin and walking into a fierce wind, I take a detour to wander around the grounds of my alma mater, Victoria College. I feel nothing as I gaze over the green lawns, watching two young men kick a soccer ball. Alma mater means “nourishing mother,” but this place was not that for me. Those four years as an undergrad in English Literature are a blur. One thing stuck: a Shakespeare lecture by Northrop Frye when he—already extremely old—told us in his quavery voice that Bach’s Mass in B Minor was the voice of God speaking. All of us bent over our notebooks and wrote that down. It sounded profound.

I was a lonely young woman. Barry Lopez writes that “It is not possible for human beings to outgrow loneliness,” and that seems true to me. Though I’m not as lonely as I was. I admire a pigeon perched in the recessed window of the Victoria University Common Room.

On the way up University back to Bloor Street, I check out the Gardiner Ceramic Museum, where I hope to see the work of contemporary ceramic artists, only to find that the main galleries are closed for renovation. I continue back along Bloor. It’s time for a coffee and I remember a Second Cup in the block before Spadina Avenue. And if that is no longer around, there’s a coffee shop in the old Jewish Community Centre (JCC), where my mother did aquafit for the last decade of her life. Back in the seventies, when it was the Young Men’s Hebrew Association, it was home to SEED, the alternative school my sisters and I went to as wild teens.

Second Cup is gone, and so are many of the other businesses on that block. Everything in life is impermanent, so I am not surprised Second Cup and Noah’s Health Foods have disappeared, and the spaces are vacant. Once upon a time there was a greasy spoon in this block where we drank coffee in thick cups, smoked cigarettes, and ate French fries. We walked over from “school” and stuffed our electric bodies into the vinyl booths, laughing, talking, flirting, mystified and excited by life. Once, for a time, my sister lived above the restaurant with her boyfriend, an apartment with burlap on the walls and plants everywhere. There’s history here.

The wine store remains. This is where we bought bottles for the meal marking my mother‘s death in February 2019. Her house is only a few blocks from this corner, and she died at home. We carried the clanking bottles through the snow. My sister made bouillabaisse and we sat around the teak table, drinking, eating, and telling our Virginia stories, stories filled with love, regret, sadness, and confusion.

I cross the street twice to the southwest corner and pull on the doors of the Jewish Community Centre, but my pull meets resistance. A security guard opens the door from the other side, just a few inches, and peers at me. “I am trying to get into the coffee shop,” I say. “No more coffee shop. Coffee shop no more,” a sort of palindrome of endings. And he closes the door in my face.

I keep walking. Surely, there is a sweet, cool, interesting café somewhere along Bloor. I am Ahab stalking the great flat white, but she’s nowhere to be found. I pass more than one Tim Hortons among the restaurants and bars still closed this cold morning, but no, I won’t go there. Cigarette butts decorate the grey pavement, evidence of parties spilling onto the street last night. Pigeons strut their stuff. I keep walking. Yes, I know Futures Bakery might be considered an interesting coffee shop, but I hold out for something else, some uncertain thing, something new, something not in the algorithm.

I keep walking. The Hungarian restaurant where we ordered dumplings and gravy and goulash soup: gone. The delicatessen and the cheese shop with a cow in the window: both gone. The café that once took up that southeast corner of Bloor and Bathurst: gone. Now there’s a Fancy Burger outlet, where you can add a syringe cheese shot to your beef patty for $1.49. This part of Bloor continues to metamorphize. Ethnic restaurants and record stores turn into cannabis shops and bubble tea counters. Used bookstores become pet pampering salons and tattoo parlours.

I am happy to see Midoco, the office supply shop, a place where you can lose yourself among the art supplies and fountain pens, is still in business. Ditto the Home Hardware.

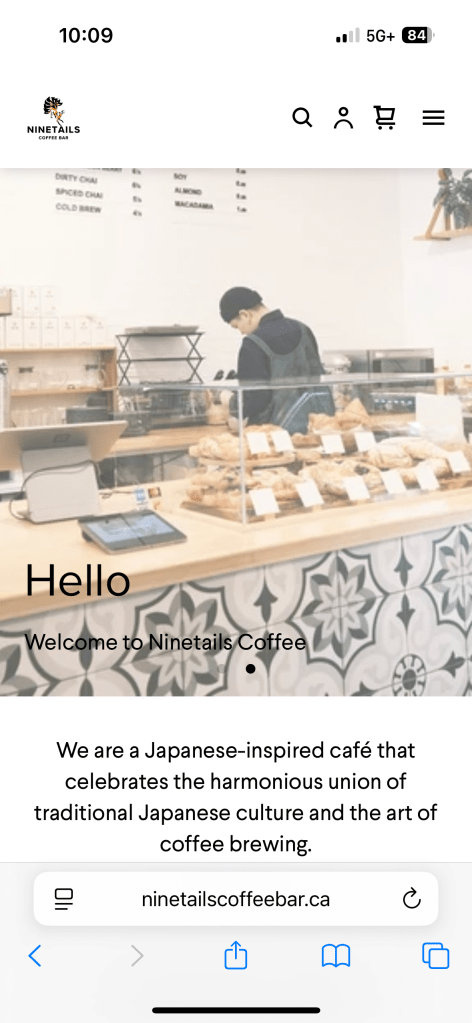

I keep walking, knowing that somewhere soon, I will come upon something interesting. I pass the small corner grocers, happy to see they still sell bargain produce and hanging pots of flowers. I pass Euclid, cross to the south side, and then, suddenly, there is an A-Frame sandwich board picturing a fox with many tails. I walk into Ninetails Coffee Bar, where two young Japanese women bustle behind a honey-coloured wood counter. White walls, a few small round tables graced by simple folding chairs. A coffee bar decorated with ceramic tiles patterned in grey, blue, and white. A full pastry case. Smiling faces welcome me.

My flat white, delivered in a short glass with a foamy fern on top, is delicious—strong and hot. While I drink my coffee I read about the coffee bar’s philosophy.

In Japanese folklore, Kitsune are foxes with mystical powers that can grow nine tails.

“we embrace the Japanese philosophy of ‘ichi-go ichi-e,’ which translates to ‘one opportunity, one encounter.’ This concept underscores the importance of cherishing every moment and every connection we make with our guests, as each encounter is unique and irreplaceable. Our goal is to provide you with a little window to Japan & Japanese culture within each visit.”

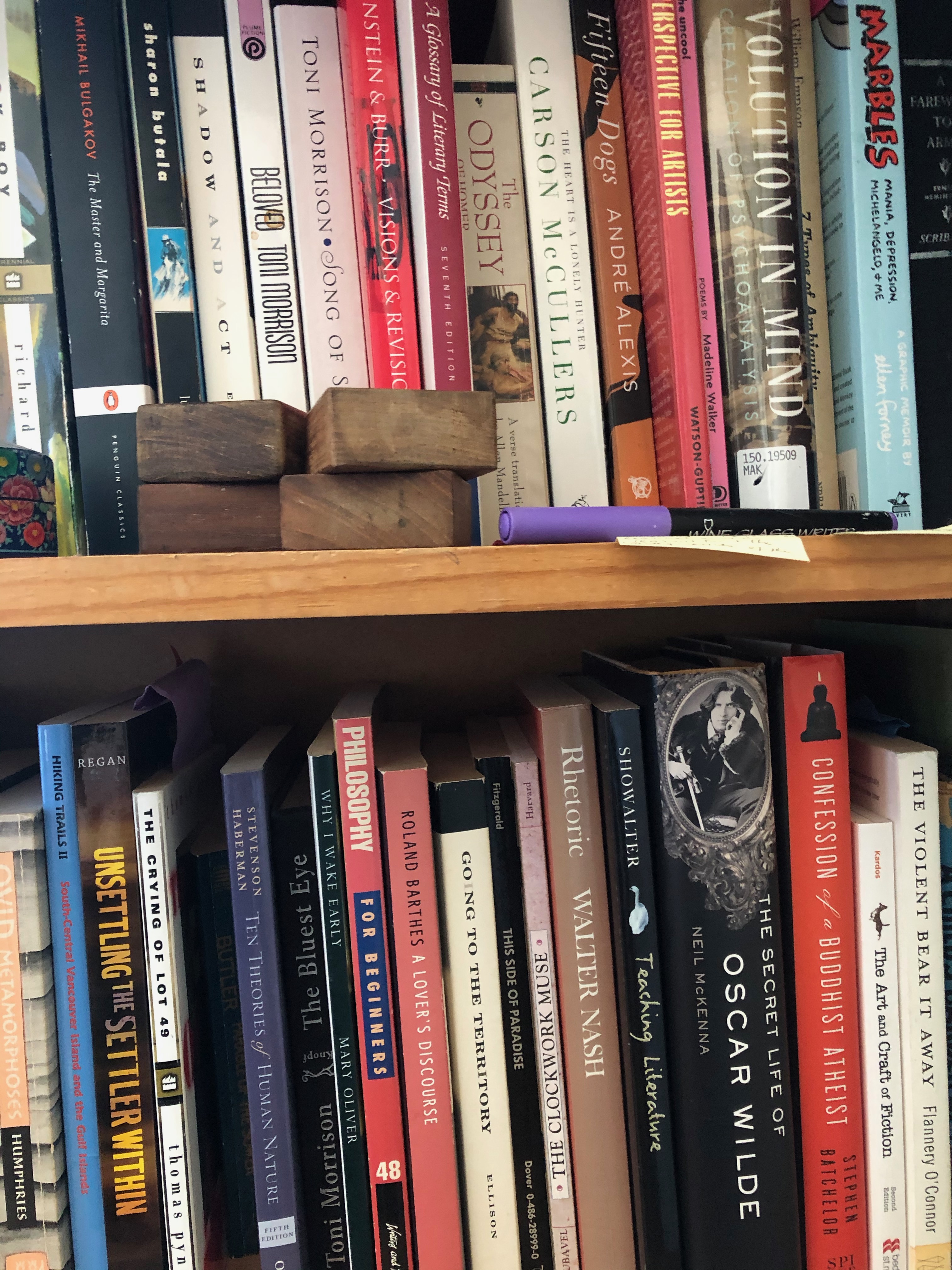

I gaze across Bloor to the north side and see, to my delight, a used bookstore that I’ll visit after I drink this coffee. It’s too easy to get lost in the past during this trip. Wandering through old neighbourhoods, remembering past experiences, feeling traces of old sadness and joy. But Toronto, like Freud’s Rome, is a metaphor for the mind. There is no denying that my personal history, etched through the decades, permeates my experience of Bloor West. I feel these vestiges of the past in my body.

But there is also the present: every moment is unique and irreplaceable.

The sun finally emerges from behind grey clouds on this cold day and streams through the glass over my table. I will never experience this moment again, as I drink this coffee, as I gaze at the people around me, the heavily inked man, the woman with green hair, as I examine the fox on the sandwich board outside, waving her many tails. She reminds me there is only one opportunity, one encounter. This is it.

A few weeks ago, I picked up Octavia Butler’s The Parable of the Sower from the cute little library on the front yard of a house around the corner. “Take a Book, Leave a Book” was painted in curlicued white letters across the blue cupboard doors. When I was a teenager, I decided I wasn’t interested in science fiction. Somehow, I only wanted to read things that were “real.” So I turned to 19th century British novels and early-mid 20th century American writers like Philip Roth and Saul Bellow. Of course I have cast my reading net much wider since then, but I still don’t tend to be drawn to science fiction or its sister genres, fantasy and horror. Yet, as I dug into Butler’s novel, I became engrossed by the young female narrator/ protagonist Lauren who is bent on survival in a dystopian America of the future. Her warrior spirit drives her to escape from the murder of her family and razing of her home in a gated community in Southern California and form a motley tribe of people all searching for safety. Due to her mother’s drug abuse, Lauren was born with hyperempathy, a disability that has her feeling other people’s pain to a debilitating degree. She develops a religion called Earthseed, whose God is Change because the only thing we can be certain of is that everything changes. What felt eerie about this novel, written in 1993, was that Butler’s portrayal of a dystopian nation read as strongly resembling Trump’s America.

A few weeks ago, I picked up Octavia Butler’s The Parable of the Sower from the cute little library on the front yard of a house around the corner. “Take a Book, Leave a Book” was painted in curlicued white letters across the blue cupboard doors. When I was a teenager, I decided I wasn’t interested in science fiction. Somehow, I only wanted to read things that were “real.” So I turned to 19th century British novels and early-mid 20th century American writers like Philip Roth and Saul Bellow. Of course I have cast my reading net much wider since then, but I still don’t tend to be drawn to science fiction or its sister genres, fantasy and horror. Yet, as I dug into Butler’s novel, I became engrossed by the young female narrator/ protagonist Lauren who is bent on survival in a dystopian America of the future. Her warrior spirit drives her to escape from the murder of her family and razing of her home in a gated community in Southern California and form a motley tribe of people all searching for safety. Due to her mother’s drug abuse, Lauren was born with hyperempathy, a disability that has her feeling other people’s pain to a debilitating degree. She develops a religion called Earthseed, whose God is Change because the only thing we can be certain of is that everything changes. What felt eerie about this novel, written in 1993, was that Butler’s portrayal of a dystopian nation read as strongly resembling Trump’s America. I always prefer books as objects over digitized texts. I love the feel and look of books. I love to explore marginalia and marks, run my hands over bindings, examine tatters and pages folded over, text that has been underlined. The other day I picked up a well worn novel (The Lotus Eaters by Tatjana Soli) from a free library that had written in the inside cover in elegant cursive, “Property of” followed by a rectangular stamp: The Cavern Hotel and Café, El Nido, Palawan. I Googled this mysterious place and discovered it is a hotel offering pod accommodations in the Philippines. So interesting. (The next day, Trip Advisor wondered if I would like to see the current rates for staying the Cavern.)

I always prefer books as objects over digitized texts. I love the feel and look of books. I love to explore marginalia and marks, run my hands over bindings, examine tatters and pages folded over, text that has been underlined. The other day I picked up a well worn novel (The Lotus Eaters by Tatjana Soli) from a free library that had written in the inside cover in elegant cursive, “Property of” followed by a rectangular stamp: The Cavern Hotel and Café, El Nido, Palawan. I Googled this mysterious place and discovered it is a hotel offering pod accommodations in the Philippines. So interesting. (The next day, Trip Advisor wondered if I would like to see the current rates for staying the Cavern.) the dark, I enter into the world of Butler’s novel, where kindness is the last good thing, where people band together in tribes because love and human relationships are all that we have, and where impermanence is the only truth. Wait a minute, all of that is sounding familiar. Is it really the future, or is it now?

the dark, I enter into the world of Butler’s novel, where kindness is the last good thing, where people band together in tribes because love and human relationships are all that we have, and where impermanence is the only truth. Wait a minute, all of that is sounding familiar. Is it really the future, or is it now?