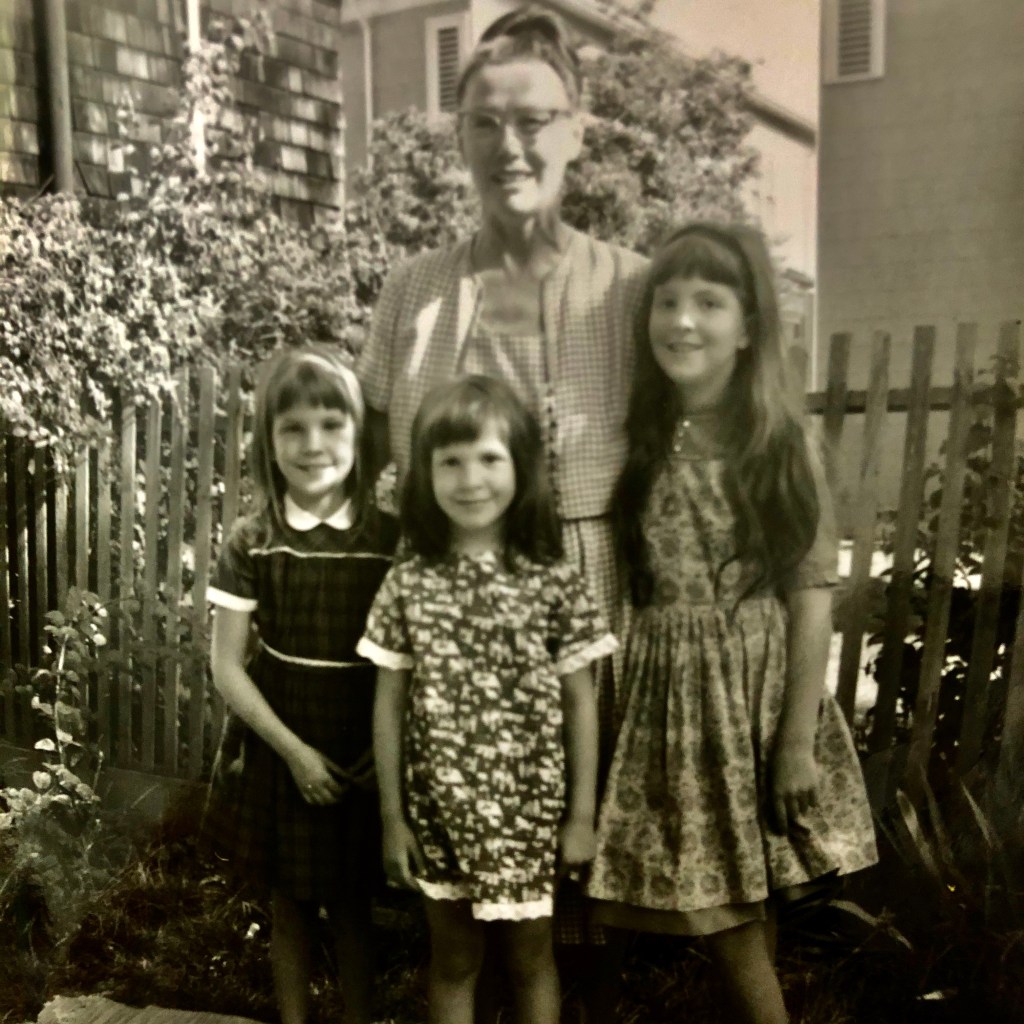

This week, I moved my office to the basement—a desk, a rug, a chair, lamps, a bookshelf full of books about writing and editing, my computer and my big monitor. I like working down here – I feel more efficient and less distracted than when my office was upstairs. I am getting ready for self-employment as an editor. Part of my moving process included going through some old papers. I came across a bag of letters from the 1960s from my adopted grandmother. Phyllis took my mother, who felt neglected by her biological mother, under her wing in the 1950s. She cherished “Ginger” and paid for her psychotherapy for years. When my sisters and I were born, we always called her Grandma, and she showered us with love, attention, and gifts.

In August 1965, when I was six, our family moved from Berkeley, California to Toronto. For several years after that, my grandmother and I wrote frequently—we missed each other. Her letters were many pages long: typed, double-spaced in Courier with cross outs here and there. She typed on thin paper, then folded the pages into sixths so they would fit into small envelopes. Much of what she wrote was about her several cats. She usually had three or four cats at a time, mostly strays she found or who found her. She never tired of describing their behaviour, their looks, their sweet antics. Today, I slipped my hand in the bag and pulled out a letter dated February 12, 1966.

Mercury retrograde has been disrupting communication since the end of January, and I’ve felt those disruptions—messages gone astray or misinterpreted. But the serendipitous reach into a bag and the pulling out, like a rabbit from a hat, a message from fifty-five years ago to the day—feels special indeed. The magic lingers today. She wrote,

February 12, 1966

Dearest Madeline:

You make me feel very lucky to have such a good little letter-writer for a granddaughter. I have two letters to answer, just as I did the last time I wrote to you. That means you are twice as faithful in your correspondence as I am.

You wrote to me on January 20th, “I don’t think I can think of much to say”, but don’t every worry about not having anything to say. If you only say “Dear Grandma, I was thinking of you and wanted to say hello. With love from Madeline.” I will be thrilled to get your letter. Just to know that you were thinking of me and just to see the envelop in the mailbox with your writing on it gives me such a big happiness when I come home from work. I get lonesome for all of you, even though I am kept busy.

I got some pictures of all of the family with my valentines, and I can see you have lost a tooth. You didn’t give that news, and anyway I suppose it didn’t seem like much news to you. But everything that happens to each of you is news to me, because I try to keep track of you in my mind and think about how you look. You may be surprised that in just the six months you have been in Ontario when the pictures were taken, you have all changed a little. You have probably grown taller too. All this is happening a long way from me, so I have to depend on your news about yourself to fill in the picture of you in my mind’s eye.

I have just re-read your two letters to see if there is anything in them I should reply to at this time. (I ought to know them by heart, I read them over enough times. The first reading is more like a mental gulp, and then I read them over and imaging you writing them, and it makes you seem closer than five thousand miles.)

Well, right off, your letter of January 20th gives me a subject to write about. In it you said that you didn’t think you would ever draw like Kathy—and this is true, I hope; because only Kathy will every really draw like Kathy. Anyone else who drew like Kathy would only be imitating here, and you know that an imitation is never as good as the original thing. You will draw like Madeline, and I think each of you are pretty wonderful, and each of you has a definite quality in your drawings that speaks for you—it is the beginning of a “style”, as it is called in the artistic world. . . .

It was in the pencil portraits of Ginger and Kenneth that the “you” in your drawings was particularly effective. . . . the pencil drawings were quite remarkable, I thought, not because they were as expertly drawn as you might have thought they should be—but because they were as they were genuine portraits in the fullest meaning of the word, not only a physical resemblance, but you caught something of the total character of your mother and father. Not only would I recognize them immediately if you hadn’t labeled the drawings, but they were well proportioned and had had an inexplicable quality I can only call “aliveness”. This means that you are both perceptive and have control over your pencil—two qualities a great many grown-up artists which wish they had.

I hope you learn all you can about the techniques of drawing and painting, but I hope even more that you hold onto the precious quality of being able to draw what you see without self-consciousness. I hope I don’t bore you with all this talk about your drawings but I just took at the envelope and looked at all of the paintings and drawings over again and I feel just as delighted with each of them as I did the first time I got them.

I was struck by how loving and lively her voice is. It reaches to me over decades, skipping over death. Her affection touches me afresh, like fingers brushing against my cheek. Her words demonstrate a lively interest in me as a person, a lovable girl with talents and potential, and her enthusiasm, her vigorous voice, still warms me as anew, even though her hands folded these pages more than half a century ago.

The letter goes on, the next four pages all about her cats: Thumbelina, Pinky, Batu, and the newest addition, Duckling. She describes driving to the mail box , and getting out of the car to mail a letter, when a small black cat comes up and mews at her. She asks the neighbourhood children walking to school whom the kitty belongs to and none of them know. She tries to shoo the cat away, but when Grandma opens the car door, the cat slides in beside her, “settling herself into a comfortable little bundle and starting to purr.” Then she writes, “What could I do? I turned the car around and took her home.”

Grandma writes she is “altogether the most unprepossessing little black kitty—and that is how I started calling her a little ‘Ugly Duckling,’ which has now been shortened to ‘Duckling’.” On page 5, after descriptions of Duckling’s warrior stance with the other cats, Phyllis writes, “She adores the sheepskin rug, standing ankle deep in the fur, purring and making biscuits with a trancelike expression on her little face.” I can see that little black cat kneading even now, deep in her pleasure, having found a refuge.

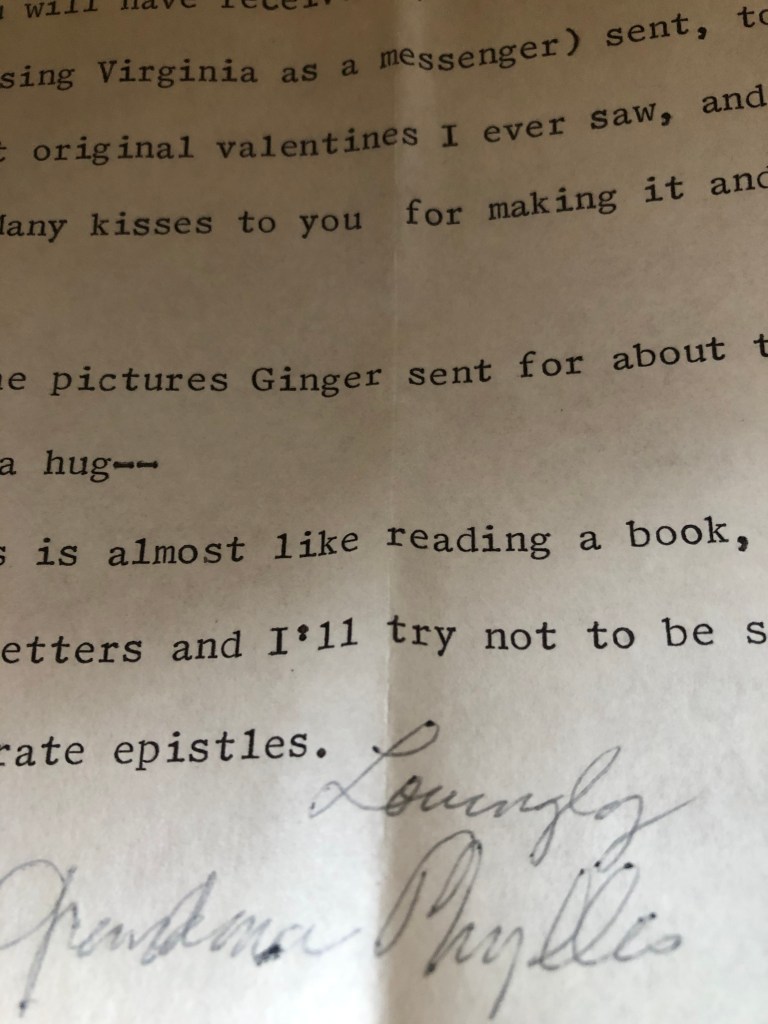

Grandma ends the letter at the end of page 6 with rhetorical flourish, “Now I come to your lovely valentine…Thank you, darling. It is one of the most original valentines I ever saw, and I dearly love what you wrote on the back. Many kisses to you for making it and sending it. …

Goodbye little sweetheart. This is almost like reading a book, isn’t it? Tell me if you get tired reading long letters and I’ll try not to be so long-winded, or divide my letters into three separate epistles.” And in pen, “Lovingly, Grandma Phyllis,” with many x’s and o’s across the bottom of the brittle paper.

Tears clumped in my throat when I read the last paragraph. “Goodbye little sweetheart.” I’d forgotten her affection for me; I’d forgotten what it’s like to be a child treasured by an adult. I’d forgotten the warm articulate voice that spoke to me in Courier typeface, that set me firmly in her pink spotlight, never talking down to me, using language so beautifully and naturally, telling me her stories. Perhaps reading her long letters planted the seed for my love of reading and writing, my love for stories, my affection for the long dash. I’d forgotten what it’s like to have an adult consider you—a small child—valuable and important, your burgeoning talents of great interest and worth remarking on.

In the universal way of impermanence, the relationship slackened over the years, which was not surprising, given our distance from one another and my encroaching adolescence. But that little magic pocket of emotion inside of me has been lit up, rosy pink, these last 24 hours. A lamp-like glow that bathes me from the inside out. I feel loved.

Happy Valentine’s Day to all of you. Thank you for reading.

Hello Madeline! I am touched by this story–almost crying myself. How great you have these letters and photos. …sounds like another world and another life–California of the 1960s, Toronto of the 1960s. I do believe your ‘Grandma’ planted some of those seeds in you that grew into your love for reading and writing. … I am so intrigued by the story of relationships between your mom and Phyllis–I will make sure to ask you about it when I see you. …. Your post sheds light onto why I (me, myself) can’t be a Buddhist — I am too much anchored to the past through similar letters and artefacts that I cherish from my childhood and from my ancestors’ lives. I stubbornly don’t want to sever these threads. What about you? (Let’s talk about this a bit later — in person)

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you, Olga! Yes, let’s talk in person about family relationships. We are alike in the way we treasure artefacts from the past. . . . I look forward to seeing you in person.

LikeLike

Thank you, a beautiful touching story!

LikeLike

Thank you, Arnie.

LikeLike

Thank you for introductions me to Virginia’s mother. Wonderful remembrance.

Love, Doug

>

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you, Uncle Doug.

LikeLike